‘Uncategorized’

“Raised on Foundations of Slime”

Jota Mombaça, Ghost 7(1-7): French Historical Maladie, Frac des Pays de la Loire, Nantes. Documentation of work in progress, courtesy of the artist, 2024. [ID: Colour photograph showing a close-up of some fabric that is wet with slime and mud, laid out on the grass after spending 4-5 weeks submerged in the River Loire. The grass is green and the colours of the fabric are red-pink, brown-grey, and black-charcoal, swirling together.]

Jota Mombaça, Ghost 7(1-7): French Historical Maladie, Frac des Pays de la Loire, Nantes. Documentation of work in progress, courtesy of the artist, 2024. [ID: Colour photograph showing a close-up of some fabric that is wet with slime and mud, laid out on the grass after spending 4-5 weeks submerged in the River Loire. The grass is green and the colours of the fabric are red-pink, brown-grey, and black-charcoal, swirling together.]

🎶 An audio version of this text can be found > here <

DRY LANDS

On a recent flight to Amsterdam, I read a chapter about the seventeenth-century Dutch landscape painter Jan van Goyen in Lytle Shaw’s book New Grounds for Dutch Landscape (2021). Shaw presents van Goyen as a guy obsessed with mud, during an age of intensifying “land reclamation” efforts in the soggy, swampy place now known as the Netherlands. It took enormous effort to pull these lowlands out of the wetness: dam and dyke building; peat dredging; draining the lakes and ponds; and erecting thousands of windmills for pumping water from the ground and sending it towards the redirected rivers and constructed canal systems . . . The process, of course, is never finished. It takes ongoing management to push the swamp away. The grand old Amsterdam canal houses lean into each other as the underground poles that stabilise them rot in the moist depths. Land reclamation fights with swamp reclamation, because the swamp always remembers where it was.

Bearing witness to the national project of separating land from water in the Dutch Golden Age, van Goyen often painted muddiness as his subject matter. He also, according to Shaw, painted as if he were re-enacting the land reclamation process. He was known for painting wet on wet—slathering his panels with puddles of gloopy oil paint before gradually differentiating legible forms and drawing them out from the primordial ooze. In Shaw’s words, he pulled his pictures “out of murky expanses of oil paint in much the way Dutch land itself was produced through pumping and draining.”1 At the same time, van Goyen’s paintings also maintained a quality of non-differentiation—signalling that the mud is still there, and that the process of separating the dry from the wet was always incomplete, always reversible. As Shaw writes:

In a culture obsessed with, organized around, and literally built on the most advanced processes of differentiating matter—especially water from dirt—van Goyen’s entire project is one of suspending this differentiation . . . Continually returning matter to its undifferentiated state, the poorly sorted substance of van Goyen’s paintings analogizes the pre-processed swamps that previously constituted Dutch land and might, in the event of flooding, envelop it again.2

I finished reading the chapter shortly before landing at Schiphol Airport. While we were waiting on the tarmac, I took out my phone and searched for van Goyen’s painting View of Haarlem and the Haarlemmer Meer (1646). I wanted to take a look at what Shaw describes as “the intermingling of land and water” in this landscape, which is more like a mudscape.3 I zoomed in on the pair of poorly defined figures in the mid-ground—figures who are, in Shaw’s words, “barely differentiated from the oozing ground plane.”4 Where is the Haarlemmer Meer? I wondered. When I looked it up, I discovered it was right underneath me. Strange feeling. All of us on the tarmac were on top of a disappeared lake; the whole wetland area was drained in the nineteenth century, and Schiphol was built on the dried-out ground. I looked out the window of the plane and tried hard to imagine the swirling, marshy terrain of van Goyen’s picture, where the ground is soft and sticky, and everything sinks into it and gets muddied by it.

“VANQUISHED BY WETNESS”

Looking at the poorly differentiated figures in van Goyen’s painting, I’m reminded of a muddy rugby match that I learned about from the artist Joseph Noonan-Ganley.5 Basically, the stadium at Cardiff Arms Park in Wales was built on land “reclaimed” from the River Taff, and it tended to get very muddy—especially during wet weather.6 On one particularly wet day in January 1970, things got so muddy that the rugby players began to lose their distinction from the ground, from the environment, and from each other. As Noonan-Ganley writes, “The boundaries of the teams’ sense of self were compromised by the mud: the application of the mud messes up the division between players. Their squad numbers taken away, their teams’ fidelity is occluded.”7 Chaos ensued. The players couldn’t control their movements; they slid around, got stuck together, struggled to remain vertical—struggled to even lift the ball up out of the mud—and ended up in a pile, all covered in muck.

Mud messes with boundaries and categorization and progress. It likes commingling and it likes horizontality. It makes heavy things sink. It makes the upright slip over. It’s very difficult to erect vertical structures on muddy grounds; they won’t stay up. Mud can introduce slowness, too. “Suddenly my feet are feet of mud; it all goes slow-mo,” sings Kate Bush in her—best, in my humble opinion—song “Suspended in Gaffa.” When someone is “swamped” with deadlines, they’re overwhelmed and struggling to move forward efficiently. When a situation becomes a “quagmire,” everything is muddled and extrication is difficult. When things get “bogged down” in bureaucracy, progress is obstructed. When playing “stuck in the mud,” getting stuck in the mud means you can’t move forward. But mud isn’t only about getting stuck. As the rugby players in Wales learned, it’s also about lubrication, slippage, and quick, unpredictable movement. Mud is a slimy substance, and, in the words of V Barratt from VNS Matrix (an Australian cyberfeminist collective self-described as “merchants of slime” who “crawled out of the cyberswamp” back in 1991), “slime is interstitial.”8 It moves through narrow openings and occupies the gaps between things.

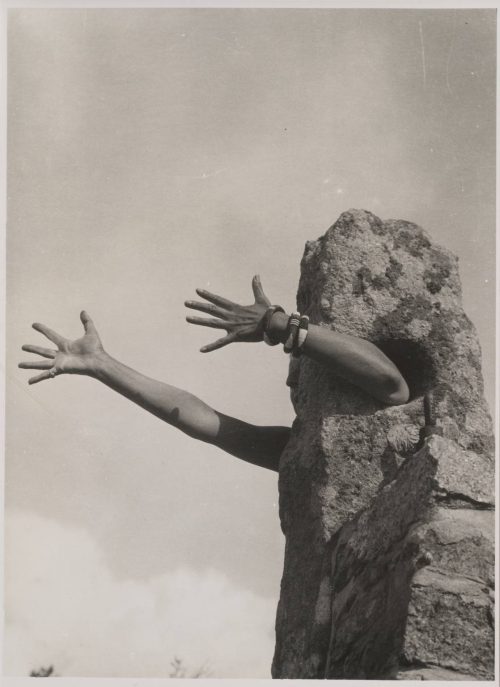

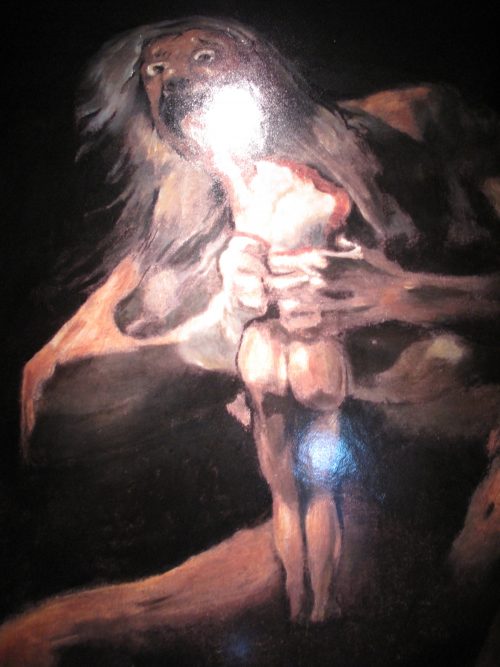

Male Fantasies (1977–1989), Klaus Theweleit’s two-volume study of the German fascist imagination, opens with an image of a vintage postcard showing a train crossing the Hindenburg Dam. It’s surrounded by tumultuous waters—with waves breaking right onto the tracks—but, in heroic defiance of the elements, the train moves full steam ahead. The Hindenburg Dam, which opened in 1927, is an 11-km-long causeway forming part of The Marsh Railway, a trainline that runs through marshlands in the north of Germany. As the point of departure for Theweleit’s study, the triumphalist image sets up one of his central themes: the fascist fear of mud. He goes on to trace a deep-seated anxiety about wetness and swampiness running through the writings of the men who formed the Freikorps military volunteer units in the aftermath of WWI. (Refusing to disarm after the war, these men banded together to suppress the revolutionary German working class and fight Soviet communism. They were crucial to the rise of National Socialism, and some of them later became high-ranking Nazis.)

Examining the Freikorpsmen’s diaries and letters, Theweleit looks at how their fear of revolution involved fears of wetness and seepage. Again and again throughout the literature, Theweleit encounters imagery of waves, tides, streams, torrents, floods, and oceanic surges that threaten to inundate society, engulf bodies, and transgress boundaries. The Freikorpsmen imagined themselves rescuing Germany “from the Bolshevistic flood.”9 Striving to become a “rock amidst the raging sea,”10 they set out to form a hard barrier against “the stream of insurgents” that “pours like the Great Deluge.”11 They struggle to dam up “the raging Polish torrent” and ensure that “the Red flood” is “finally flushed away.”12 Swampy metaphors of mire, mud, and morass also abound. The Freikorpsmen imagined themselves staving off “the muddy tide of revolution” just as “the wave of Marxist mire was cresting,”13 so that Germany would not sink “into the Red morass.”14

Similar metaphors of watery inundation have, in more recent decades, been a staple of anti-immigration racism. In 1978, Margaret Thatcher declared that “people are really rather afraid that this country might be rather swamped by people with a different culture.” In 1996, Senator Pauline Hanson announced, in her first speech to the Australian Parliament, that the nation was in danger of being “swamped by Asians.”15 The mainstream media of the Global North frequently reports on “the streams of migrants” and “waves of refugees” that are “pouring in,” “flowing in,” and “flooding in.” “Migrants Flood Greek Island of Lesbos,” reads a New York Times headline. “This tidal wave of migrants could be the biggest threat to Europe since the war,” declares the Daily Mail. The anxiety that is evoked through these dehumanizing ecological metaphors is always related to an imagined loss of control. It’s a dread of slipping; of contamination; of dissolution; and of losing white homogeneity and dominance.

Theweleit suggests that the Freikorpsmen of the early twentieth century feared the swamp because they feared drowning and engulfment. They had to stand as hard pillars of dryness and security so that the murky depths of revolution would not swallow them up. Part of the terror of the swamp was that it could “absorb objects without changing in the process.”16 It was thus dreaded as an entity that held “hidden things, things from secret realms and from the domain of the dead.”17 The “soldier males,” as Theweleit calls them, strived to erect themselves as heroic, towering bodies with fixed boundaries. They stood upright, “not just clearly, but also honestly.”18 The swamp was not honest; it was a deceptive realm of hybridity, ambiguity, “Jewish” impurity, and “feminine” wetness and softness. It was where substances mixed, edges broke down, and movements were multidirectional. The movement of the train in the Hindenburg Dam postcard is clearly directed; the train is elevated above the water, and literally on track with a pre-determined destination. The water down below, by contrast, is nonlinear; it moves in multiple directions at once, with fleeting eruptions of force that slosh around unpredictably.

Image from the preface of Male Fantasies Volume 1: Floods, Bodied, History (1977) by Klaus Theweleit. [ID: A black-and-white image of a vintage postcard showing a train moving full steam ahead even though it is surrounded by tumultuous waters and breaking waves.]

Image from the preface of Male Fantasies Volume 1: Floods, Bodied, History (1977) by Klaus Theweleit. [ID: A black-and-white image of a vintage postcard showing a train moving full steam ahead even though it is surrounded by tumultuous waters and breaking waves.]

If the fascist dread of the swamp relates to fears of wetness, disorder, dissolution, horizontality, softness, spillage, and uncontainability—as well as fears around losing the hard sovereignty of the autonomous self—what does the inverse of this dread look like? What would it mean to embrace mud and its capacity for defilement? To get into the wetness of the ground, and to let it get into you? To want to be where things are messy and in unpredictable motion? To want to move like slime, oozing through interstitial spaces and lubricating the slippage of things? To relate to the world through its squishy permeability? To appreciate the ground as a responsive and relational place—a place that receives and remembers things, without striving for vertically erected permanence? To, in the words of C. Riley Snorton, “play in the mud, which is to say, to refuse formal techniques of classification”?19

Ursula K. Le Guin wrote a tiny text called “Being Taken For Granite,” in which she declared, “I wish that those who take me for granite would once in a while treat me like mud.”20 Granite, Le Guin notes, appears upright, immovable, and unchangeable—it “makes pinnacles” and “does not accept footprints.”21 Mud, on the other hand, “lies around being wet and heavy and oozy and generative.”22 Le Guin acknowledges that such squishy, unstable footing can leave some feeling insecure and resentful. “Maybe they fear they might be sucked in and swallowed,” she muses.23 But she wants to embrace her muddiness—her capacity to remain low down in the mess of relational entanglements and their movements, which leave her “all full of footprints and deep, deep holes and tracks and traces and changes.”24

The subversive potential of mud can also come into play in a more literal sense. See, for instance, “Mud and ACAB,” a short section of the pamphlet We Are ‘Nature’ Defending Itself by Isa Fremeaux and Jay Jordan of the Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination. In this publication, Fremaux and Jordan offer an account of their involvement with the ZAD (“Zone to Defend”) in France, a rural protest camp and experiment in commoning, with dozens of collective living spaces occupying over four thousand acres of wetlands, fields, and forests. For decades, the farmer and squatter communities of the ZAD have fought to defend the territory and prevent an unnecessary airport from being built there—while the French state has repeatedly tried and failed to evict them.

Recalling a particularly brutal eviction attempt in 2012, Fremeaux and Jordan write about how the mud became an accomplice for the residents. Battalions of riot police were sent in from across France, but as they tried to navigate the soggy terrain that they had no understanding of, the weight of their armament caused them to sink and succumb “to the earth’s wet grip.”25 As the residents began throwing handfuls of mud at them, the cops became increasingly disoriented and immobilized. The sludge showered onto their visors, blocking their vision. Some of the residents found that if the mud was aimed just right, it would slide down and fill the cops’ body armour so that they could no longer bend at the knees, and they would start toppling down into the gloop.26

The 2012 eviction attempt was a spectacular failure, and the ZAD has since succeeded in stopping the new airport project. For Fremeaux and Jordan, the wetness of the ground offered more than just a useful material in this fight; it also became a part of their political imagination. As they wrote at the time:

The word humble (like the word human) has its roots in humus, it means to literally return to earth. Perhaps the future will be built by heroic acts of humility rather than arrogant temples to growth. Perhaps civilization’s dream to suck this zone dry with its concrete and tarmac, steel and plastic will be vanquished by wetness.27

RUINS IN THE MARSHES

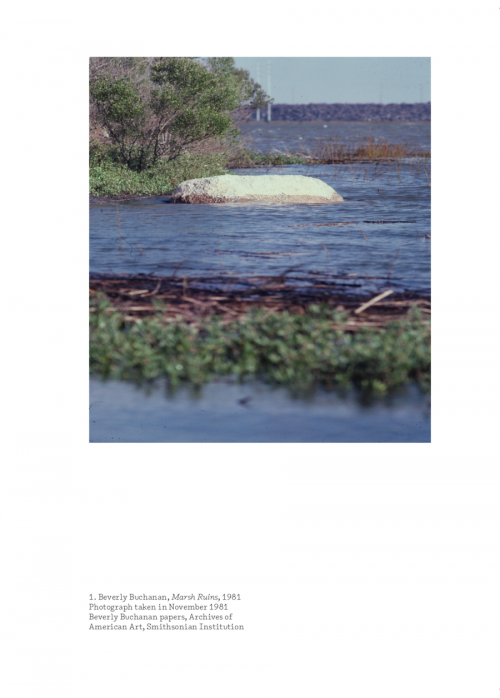

My interest in wet grounds began with my research on the artist Beverly Buchanan and her Marsh Ruins, an environmental sculpture erected in the intertidal coastal wetlands of Brunswick, on the southeast coast of Georgia, in 1981. The work is still there: three solid, ruinous boulders, built from concrete and tabby, which have been slowly crumbling and descending into the mud for more than four decades.

When she was in the early stages of planning the Marsh Ruins, Buchanan wrote, in a letter to her friend Lucy Lippard, that she was trying to imagine a site near water. “Near the ocean would be ideal,” she said, “so that eventually the piece would be ‘taken in.’”28 During this era, Buchanan often worked with bodies of water as sites of ecological entanglement, and as agents of sculptural formation and deformation. She lived in Macon, a small town in central Georgia, and she made several artworks with the Ocmulgee River, sending floating objects off to be pulled away by its currents, and leaving one of her sculptures submerged in its waters. When she travelled to Denmark in the summer of 1980, she made an ephemeral stone work, called 6-Piece Abandoned Sculpture, at the water’s edge on a beach at Kronborg Castle. As the tides came in and started rearranging the abandoned fragments, she took a series of photographs to document the work’s undoing. The Marsh Ruins, similarly, were constructed in the liminal zone where the water meets the land, and when the tides are high, they become partially submerged.

Beverly Buchanan, Marsh Ruins (1981). Photographed by Amelia Groom, April 2019. [ID: Colour photograph showing a marsh landscape with three stone boulders nestled among tall grasses. The still water behind them reflects the sky above.]

Beverly Buchanan, Marsh Ruins (1981). Photographed by Amelia Groom, April 2019. [ID: Colour photograph showing a marsh landscape with three stone boulders nestled among tall grasses. The still water behind them reflects the sky above.]

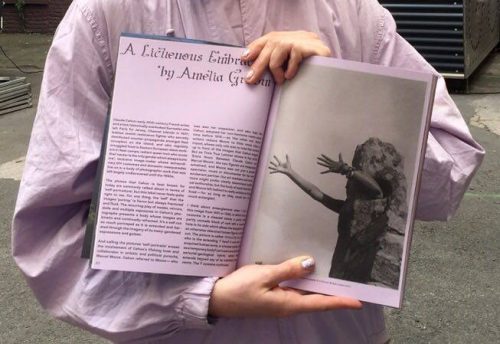

After travelling to Brunswick to see the Marsh Ruins back in 2019, I wrote a short book on the work. I spent some time thinking about Buchanan’s approach to ruination and what it means for an artist to make sculptures that are, at their very outset, conceived as “ruins.” With hindsight, I can say that I spent far less time in the book grappling with the other word in the work’s title: “marsh.” The marshland is, in many ways, a deeply significant site to choose for a major environmental sculpture in the deep south of the US. Things that are erected on muddy grounds are destined to sink and fall, messing with figure/ground and nature/culture bifurcations on their way down. Wetlands are zones of instability and ambiguity; they’re difficult to traverse, difficult to understand, and difficult to instrumentalise in accordance with colonial logics. In her work on “ecologies of resistance” in the plantation zone, Monique Allewaert describes how the swamp “stymied colonial armies and cartographers” and “compromised the order and productivity of imperial ventures, from explorations to plantations.”29 Throughout the southern landscapes that Buchanan grew up in—and later made work in dialogue with—swamps are also highly significant in histories of Black fugitive freedom, as sites that harboured maroon communities and their alternative life-worlds.

I have recently been trying to think and read about the aesthetics of mud and the significance of swamps in histories of counter-colonial resistance. This essay is an attempt to bring together some of the myriad strands of thought and research that I am moving through, and some of the artists, activists and scholars whose work has been guiding me. The text can be read as an oblique postscript to the Beverly Buchanan: Marsh Ruins (2021) book.30 There is always more to say about Buchanan’s inexhaustible work; like a marshland ecology, the Marsh Ruins are a site of uncontainable, leaky abundance. While this essay is not directly “about” Buchanan, she is very much a part of its ecology—and its lines of inquiry have seeped out from my encounter with her swampy environmental sculpture.

SUCKED IN

I opened this essay with van Goyen’s mudscapes. His paintings bear witness to early seventeenth-century Dutch land reclamation practices on a local scale, but these practices were also globally entangled. He was born in 1596—the very year that marks the start of the Dutch involvement in the transatlantic slave trade. He was six years old when the Dutch East India Company (VOC) was founded in 1602. By the time he painted View of Haarlem and the Haarlemmer Meer in 1646, the “humanist prince” and human enslaver John Maurice had already returned to Europe after his years as the governor of “Dutch Brazil,” the first Dutch Atlantic slave society and plantation colony, which was built on the stolen Indigenous lands of the north-east coast of Brazil. Elizabeth A. Sutton describes how Mauritsstad—which Prince Maurice founded as the capital city of Dutch Brazil—was, like so much of Holland, constructed on low-lying marshy lands that were drained and “reclaimed” through a canal system.31

The Dutch endeavoured to remake the local environment in their own image wherever they went in the so-called New World, including “New Amsterdam,” the settlement founded in 1625 on the swampy grounds of the stolen Lenape territory that is now known as Lower Manhattan. Memories of the suppressed watery past are still held in the financial district’s heavily paved streets, which now support the extreme vertical reach of towering skyscrapers. The curve of Pearl Street is the curve of the original shoreline; the name was “Parelstraat” in Dutch—a reference to the prominent Lenape shell midden that the settlers destroyed, using its white oyster shell fragments to pave the road. When the settlers used landfill to extend the shoreline into the East River, they built a street that runs in a straight line in front of Pearl Street. This street was often washed over with the salty waters of the river during high tide, which is why it has the name Water Street.

Dutch mud management techniques were also imported to (the region now known as) Indonesia and to the Dutch colonies in South America. Shortly before he was assassinated, the Guyanese Marxist historian Walter Rodney described how Dutch enslavers established their plantations along Guyana’s coast by overseeing the transformation of the region’s swampy ecology through techniques of “sea defense” and land reclamation. “The people of the Low Countries gave to the world the concept of a polder, referring to a piece of usable land created by digging and then draining a water-covered area,” Rodney writes, noting that the arduous work of making the land “usable”—by draining the mud and constructing elaborate systems of canals, dams and dykes—was entirely dependent on the labour of generations of Black and Indigenous enslaved and indentured workers.32

In her study of the intertwined histories of cartography and capitalism in the Dutch Golden Age, Sutton looks at the significance of the Beemster polder project that was founded just north of Amsterdam in 1608. The Beemster was a huge marshy lake area that was drained over several years and made into a dry grid of parcelled-out property. As the largest polder in the Netherlands and the first corporate land reclamation investment scheme, the Beemster was hailed as “a triumph over water” and “a statement of Dutch power over nature.”33

When the English embarked on major land reclamation projects in the first half of the seventeenth century, they turned to Dutch drainage engineers and their “literally world-changing technology.”34 The General Drainage Act was passed in 1600 for “making dry and profitable” many hundred thousand acres of marshes in the English Fenlands.35 Vittoria Di Palma has shown that while the region was dismissed as a “wasteland” and “mere quagmire,” the Fens had, in fact, long been a bountiful commons for local peasant foragers. She notes that the Dutch “produced the maps, the engineers, the venture capitalists, and, in many cases, the workers who remade the Fen landscape to fit a different model of productivity.”36 The result was a land “no longer held in common, but now divided into plots, traced out, numbered, and ready to enter the realm of private rather than communal property.”37

THE SWAMP: AN INSURGENT ECOLOGY

It should be noted that the draining of swamps for purposes of crop cultivation is not necessarily tied to colonial systems. In her book Black Rice: The African Origins of Rice Cultivation in the Americas, Judith A. Carney shows how the plantation economy along the South Carolina and Georgia coast—the area where Buchanan built her Marsh Ruins—was completely dependent on the knowledges and skills that were brought by enslaved people from regions of West Africa where coastal wetland reclamation had long been practised.38

But racial capitalism changes everything. In Sylvia Wynter’s formulation, “Western Man” initiates an entirely new relation with the natural environment—one in which, as Descartes proposed in 1637, “we . . . render ourselves the lords and possessors of Nature.”39 According to Wynter, this new relation only comes to realize itself “with the discovery of the New World and its vast exploitable lands.”40 Previously, she suggests, all societies existed in what the Négritude poet and critic Léopold Sédar Senghor describes as the “dual oscillatory process in which Man adapts to Nature, and adapts Nature to his own needs.”41 But under what Wynter refers to as the “impulsion of the market economy,” this kind of reciprocity between humans and nature was lost.42 Nature was converted into land, “conceivable only in terms of property, laid bare of myth, custom, tradition,” she writes.43 The catastrophic brutality of the Middle Passage is an inextricable part of this shift, since land, “if it were to function as land, needed not men, not communities, but so many units of labor-power.”44

When environments and racialized bodies are supposed to be reduced to property that is rationally utilized in service to capital, the swamp presents a problem. Christian morality already had a long history of “satanizing the swamp” and condemning wetlands as sites of evil and hellishness—as Rod Giblett has shown through readings of Beowulf, Dante, Milton, Tolkien, and other canonical texts that are infused with Christian traditions of theologizing the landscape.45 When it comes to the reduction of nature to land as privatised, profit-making property, wetlands are frequently denigrated as uninhabitable, impenetrable and unnavigable zones that needed to be “improved” and “civilized” through dredging, draining, and drying out.46 Through the eyes of the colonizer, the swamp was associated with rot and stench and death and disease and pollution and mess and monstrosity and femininity and waste and danger and loss.

In her cultural history of the Okefenokee Swamp in southeast Georgia (situated just inland from where Buchanan built her Marsh Ruins), Megan Kate Nelson describes how the muck and mire of the swamp stymied the military actions of US soldiers in their war against the Seminole people. Uncontainable and untameable, squishy and trembling, the swamp came to embody their failure to achieve “control over nature and power over other people.”47 Swamps also frustrated colonial efforts in cartography and stable categorization; to be rendered legible, mappable, divisible, and predictably productive, the wetlands needed to be turned into dry lands.

Ecologically, the effects of this western aversion to the swamp have been disastrous. Ecologists estimate that as much as 87 percent of the planet’s wetlands have been made to disappear in the last three centuries.48 With that disappearance comes extreme loss of life—and of complex life-systems. Wetlands host remarkable biodiversity; one statistic says that wetland areas currently make up about five percent of the surface of the planet, but more than forty percent of all species live or breed in them. They support diverse food systems and provide crucial stopover points for migratory birds. They can absorb and store vast amounts of carbon, which means substantial greenhouse gas emissions result from their drainage and destruction. Wetlands filter the groundwater by trapping sediments and pollutants. Since they can sponge up and slowly re-release water, they also act as buffer systems protecting from storms, floods, droughts, rising sea levels, and shoreline erosion. When wetlands are destroyed, so too is this protection.

Colonial aspirations for absolutely totalizing environmental control and rationalization were, however, never fully achieved. There were always swamp areas that remained beyond the reach of white instrumentalization and surveillance in the New World—and, as a result, these areas became a primary locus of marronage and Black fugitive freedom. Resisting recapture by using intimate understanding of the wetland ecology, self-liberated Black maroons were sheltered in the depths of the swamp, often living alongside dispossessed Native people, white felons and vagabonds, and other rebels and outcasts. This was certainly the case in the landscapes of the southern US where Buchanan lived and worked—with places like the Great Dismal Swamp of Virginia and North Carolina, where thousands of the formerly enslaved and their descendants found refuge and formed alternative worlds throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

The lush ecology of the swamp provided sustenance and myriad protections to those who fled from bondage and racial violence. The density of growth could be a shield that muffled sound and occluded visibility—and the muddy wetness could help to mask the body’s smell, so that the vicious bloodhounds trained by plantation owners and patrollers would lose their scent trail. At the same time, the conditions were often extremely harsh. Harriet Jacobs writes, in Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861), about hiding out as a runaway in Snaky Swamp, an area of the Dismal Swamp in Chowan County, North Carolina. She was ill and feverish and terrified of the snakes that crawled all over her, but she recalls that “those large, venomous snakes were less dreadful to my imagination than the white men in that community called civilized.”49

Jota Mombaça, Ghost 7(1-7): French Historical Maladie, Frac des Pays de la Loire, Nantes. Documentation of work in progress, courtesy of the artist, 2024. [ID: Jota stands at the top of a spiral staircase on the outside of a building. There’s grass and a grey sky in the background. Jota is opening one of her sunken textile Ghosts, and it looks like a huge dirty tongue, all pink and muddy and in motion.]

Jota Mombaça, Ghost 7(1-7): French Historical Maladie, Frac des Pays de la Loire, Nantes. Documentation of work in progress, courtesy of the artist, 2024. [ID: Jota stands at the top of a spiral staircase on the outside of a building. There’s grass and a grey sky in the background. Jota is opening one of her sunken textile Ghosts, and it looks like a huge dirty tongue, all pink and muddy and in motion.]

It was precisely because these zones were so difficult, and so reviled, that the swamp offered refuge from white society. Willie Jamaal Wright has written about the extent to which the practice of marronage was incumbent on the existence of “unruly environments”—swamps but also high mountains, dense forests, and other spaces that were consigned as inaccessible, inhospitable, not yet profitable, and that were therefore “illegible within the spatial imaginary of the participants of the plantocracy.”50 In Wright’s words:

Landscapes of marronage are those difficult terrains that marginalized, hunted, and exploited people have made habitable—areas where communities have taken a desire for liberation and merged it with an ignored and undervalued environment to gain liberties in opposition to repressive administrations.51

In this sense, the enslavers were right to fear the swamp. As a site of resistance and Black and Indigenous fugitivity, the swamp was a threat to the racial hierarchies of the settler colonial order. Kathryn Benjamin Golden has argued that the Great Dismal Swamp did more than harbour fugitives and maroon communities; its presence in the landscape also emanated the possibility of freedom and insurrection. This is what Golden terms the “insurgent ecology” of the Dismal Swamp: throughout the surrounding areas, the swamp’s looming presence “beckoned defiance of oppressive law and order” and “offered physical encouragement to enslaved insurgency and rebellion.”52

“SINKING COULD BE AN ELEVATION”

This essay is accompanied by a series of images from Jota Mombaça, an artist whose work over the last several years has been engaged with watery submersions, mud inscriptions, and what she refers to as “the radicality of sinking.”53 Mombaça was born in Natal, a port city that was the target of the Dutch invasion of Brazil in 1633 (for a brief time, the city was, just like Manhattan, known as “New Amsterdam”). While she was an artist-in-residence at Rijksakademie, Amsterdam, Mombaça became attuned to the murky depths of the city’s canals. She began making contact with these opaque repositories through a sculptural practice that involves rituals of submersion, immersion, and re-emergence. Bundles of fabric are chained up and lowered into the waters, where they are left for weeks on end, to become what Mombaça refers to as “Ghosts.” When they are eventually pulled back up, the fabrics are marked by the undoings of grime and time. They may have accrued frayed corners, clinging sediments, rust stains, traces of interaction from fish and other forms of underwater life, scratches and snags from encounters with rocks or other submerged entities, and all kinds of warpings and impressions from the algae, the salts, and the muddy depths.

Jota Mombaça, Ghost 7(1-7): French Historical Maladie, Frac des Pays de la Loire, Nantes. Documentation of work in progress, 2024. Photography by Sarah Bogard. [ID: Colour photograph of an anonymous figure in black pulling one of Mombaça’s sunken textile bundles up out of the water (or lowering it down?) with a metal chain. The water is murky and bubbling.]

Jota Mombaça, Ghost 7(1-7): French Historical Maladie, Frac des Pays de la Loire, Nantes. Documentation of work in progress, 2024. Photography by Sarah Bogard. [ID: Colour photograph of an anonymous figure in black pulling one of Mombaça’s sunken textile bundles up out of the water (or lowering it down?) with a metal chain. The water is murky and bubbling.]

“In order to be converted into a Ghost,” Mombaça says, “the linen and the metal just have to wait while the underwater forms and deforms them.”54 It’s impossible to predict what kinds of formations and deformations will arise. Since a large part of the process is literally out of the artist’s hands, there is a necessary acceptance of the fact that she is not in a position of total control. But it goes beyond acceptance; there is also enjoyment and relief found in the loss of containment and control. As the artist suggests in her video waterwill (2022), the blessing of decomposition is that it offers an “abolition of progress and order.”

“I like to relate to my practice not as its master but rather as its channel,” Mombaça says.55 With her notion of “the radicality of sinking,” she refers to “the process of abandoning oneself into the water’s embrace, giving up the fantasy of control, and allowing water to take hold.”56 There is deep resonance here with the practice of Buchanan, another artist who worked with water as a historical repository, as a hiding place, and as a force of transience and transformation. Like Mombaça, Buchanan refused to occupy the position of the all-controlling master. She was very patient and precise in her intentions for her sculptures, but she was also always concerned with listening to her materials and letting them exist in evolving relation to their settings. She enjoyed stepping back and watching her creations move away from her authorial intentions, and she celebrated the pleasure she found in relinquishing control—as can be seen, for instance, in the playful calendar that she made for friends with the title Out of Control (2000).

Jota Mombaça, Ghost 7(1-7): French Historical Maladie, Frac des Pays de la Loire, Nantes. Documentation of work in progress, courtesy of the artist, 2024. [ID: Jota is inspecting or arranging one of the sunken textile pieces, which has been hung up to dry. The fabric is frayed and torn, and the mud has left intricate patterns.]

Jota Mombaça, Ghost 7(1-7): French Historical Maladie, Frac des Pays de la Loire, Nantes. Documentation of work in progress, courtesy of the artist, 2024. [ID: Jota is inspecting or arranging one of the sunken textile pieces, which has been hung up to dry. The fabric is frayed and torn, and the mud has left intricate patterns.]

Throughout Mombaça’s sunken works, there is a commitment to being, as she puts it in her 2022 poem Visa Denied, “in touch with the mud, as in, engulfed by its embrace.”57 My own thinking on mud and swamps is very much indebted to Mombaça’s practice and the conversations we have had around it, which I hope will continue. In the years since her first experiments with the Amsterdam canals, the artist has gone on to work with other bodies of water: the Venetian Lagoon, the San Francisco Bay, the Waldsee Lake in Berlin, and—in the recent body of work that is depicted in these photographs—the Loire River in France. There is always site-specific research and response, but, at the same time, Mombaça wants to relate to the waters as figures of interconnectedness and global historical entanglements. In her words, the bodies of water “speak of place, but they also defy locality, as what is constitutive in every relationship they form with the sunken textiles is one of currents and motion.”58

Rather than representing a site through the depiction of discreet objects, the Ghosts are images that are gradually imbued with their settings, including the movements and layers of time that are held within them. For Ghost 7(1-7): French Historical Maladie, a recent body of work produced at Frac des Pays de la Loire in Nantes on the west coast of France, Mombaça worked with the heavily polluted and profoundly haunted waters of the Loire River where it meets the tidal surges of the Atlantic Ocean. This is a site where the Atlantic seeps into the ostensibly solid and delineated land of the European continent. “Deeply marked by the development of global logistics and colonial expansion, the Loire-Atlantique axis is one of revolted waters, unpredictable tides and decomposed bodies,” Mombaça remarked at the time of production. She continued:

The mud is abundant, their smells are pungent . . . So much hurt that is impossible to translate, and yet, in the offerings of the river, I found this beauty to which I am grateful. A terrible beauty that unites all of us, the colonized, through the common acknowledgment of the seeds of disintegration rooted in colonial modernity . . . With the Loire, I extend the rotten tongue of our anti-colonial dissatisfactions. I rant, I curse and I vomit: these hauntingly beautiful ghosts which are fractures of a common language.59

Jota Mombaça, Ghost 7(1-7): French Historical Maladie, Frac des Pays de la Loire, Nantes. Documentation of work in progress, courtesy of the artist, 2024. [ID: The image is similar to the one that appears at the very top of this essay, with the wet, muddy textiles laid out on the grass. Here, there’s some more detail of the patterns left in the fabrics, with slimey-black, pinky-reds, and greeny-greys.]

Jota Mombaça, Ghost 7(1-7): French Historical Maladie, Frac des Pays de la Loire, Nantes. Documentation of work in progress, courtesy of the artist, 2024. [ID: The image is similar to the one that appears at the very top of this essay, with the wet, muddy textiles laid out on the grass. Here, there’s some more detail of the patterns left in the fabrics, with slimey-black, pinky-reds, and greeny-greys.]

PLOT(TING)

This essay was commissioned for a (Dutch) online platform that is dedicated to “the plot” as conceptualized by Sylvia Wynter in the 1970s. The garden plots or “provision grounds” were small areas of land that were cultivated by the enslaved in the shadow of the plantation, as a means of sustenance and survival. In texts including her unpublished manuscript Black Metamorphosis: New Natives in a New World and her article “Novel and History, Plot and Plantation,” Wynter compares the ideology and spatial logic of the plantation to that of the plot. …

The plantation spread itself over the most fertile and desirable land, while the plot was consigned to small, marginal, difficult terrains at the plantation’s edges. The plantation grounds existed under regimes of intense scrutiny and surveillance, while the plot was often clandestine, and tended “after hours.” While the plantation flattened out and instrumentalised the ground for maximally efficient monocultural production—with the resulting product sent far away (for “a world of abstract exchange value”)—the plot was for growing food in response to local needs, as part of the immediate social context, through “concrete use value.”60 On the plantation, the slave “would represent the extreme case of alienation . . . dominating nature to create a product which was alien to his own needs, and which alienated him from them.”61 On the plot, however, “his position was a dual and dynamic relationship in which he adapted himself to nature and also transformed nature.”62

Wynter does not simply romanticize the plot as wholly exterior to the plantation system. She observes that the plot and the plantation originate together “in a single historical process,” and that the plantation masters “gave the slaves plots of land on which to grow food themselves in order to maximise profits.”63 Crucially, however, this is not the whole story. It is in the undervalued and, therefore, relatively under-surveilled zones of the provision grounds that Wynter locates the possibility for the flourishing of African diasporic folk cultures and “cultural guerilla resistance.”64 The plot was “an area of experience which reinvented and therefore perpetuated an alternative world view, an alternative consciousness to that of the plantation,” writes Wynter. “This world view was marginalized by the plantation but never destroyed.”65

The alternative consciousness that was possible in the interstitial space of the plot was antagonistic to the ecocidal rationale of the plantation. “While the ideology of the masters stressed the rights of property, the world-view of the African slaves remained based on a man’s relation to the earth and, concomitantly, to the community,” writes Wynter.66 The enslaved “transplanted to the plot all the structure of values that had been created by traditional societies of Africa.”67 In these societies, the earth was the basis of the community’s existence, and “could not be alienated as private property.”68 On the plantation, the earth was turned into land where the labour-power of the enslaved contributed to “the technical conquest of nature.”69 On the plot, however, “the land remained the Earth—and the Earth was a goddess: man used the land to feed himself; and to offer first fruits to the Earth; his funeral was the mystical reunion with the earth.”70

Édouard Glissant also identified the plot as a possible site of counter-colonial environmental praxis. Speaking with filmmaker Manthia Diawara while sitting outside in the sun in his native Martinique, the poet and philosopher of opacity and relationality emphasised the fact that cultivating plants in such small, cast-off spaces meant cultivating intimate knowledge about how different species could grow alongside each other while protecting and nurturing one another through subterranean relations. The plantation had orderly rows of a single crop laid out across a cleared field. In contrast to this coercive monoculturalism and hyper-legibility, Glissant describes how the provision grounds—which he refers to as “jardin créole”—were secretive sites of diverse multiplicities and cross-species interdependencies. “In a very narrow space,” he says, “they were able to grow dozens of different types of trees, different scents. Coconuts, yams, oranges, pines, dachines, choutchines, sweet potatoes, cassava. They did it in such a way that the plants mutually protected each other. It was the essence of the creole garden.”71

To consider the plot in this way is to consider the edges of the physical space of the plantation, as well as the limits of its (genocidal, ecocidal, and epistemicidal) violence. The worldviews that were sustained in the provision grounds were, in Wynter’s words, marginalized “but never destroyed.”72 So what happens if the swamp is brought in to triangulate the plot/plantation dialectic? These two zones, the plot and the plantation, do not account for the entirety of the eco-historical setting. While many wetlands were drained and cleared to facilitate settler productions of space, there were always those recalcitrant terrains that remained—however temporarily—beyond the reach of total surveillance, legibility, and extractive productivity. Existing as it did in a marginalized relation to the plantation, the plot could be a place for plotting escape; a place where the enslaved could gather, organise, and imagine otherwise. Existing as it did even further away from the land that was valued as rationally productive, the swamp could sometimes be the setting into which the self-emancipated would flee, either as a stopover point or as a more permanent refuge.

The swamp is not born from the same historical process as the plantation and the plot. It predates the racialising “impulsion of the market economy,” and it continues even after the imposition of that impulsion onto ecologies, bodies, and worldviews.73 And, unlike the expansive fields of the plantation and the narrow plots of the provision grounds, the ecology of the swamp defies clear delineation. It’s a planetary figure of seepage and interconnectedness—spatially as well as temporally. It can be difficult to say where the swamp begins and ends.74 The swamp exists in the shifting and unknowable depths; even when it has been drained, you can never be sure when or where its suppressed wetness might reappear.

“The pestilent marsh is drained with great labour, and the sea is fenced off with mighty barriers,” wrote Scottish Enlightenment philosopher Adam Ferguson. “Elegant and magnificent edifices are raised on foundations of slime.”75 Ferguson was describing the linear march of progress from “rude nations” to property-based civilization. But, as I’ve attempted to show, foundations of slime open up nonlinear and non-triumphalist ecologies of impermanence. The swampy muds bubble up into the foundations of Amsterdam’s grand canal houses, which were built with wealth accrued from the transatlantic slave trade. The muds seep into the reclaimed land of the rugby stadium, making a mess of differentiation. They’re gradually swallowing up the Marsh Ruins, as Buchanan always imagined they would. They make contact with Mombaça’s sunken textiles, enacting decomposition as a means of inscription, and becoming Ghosts who announce that the past is still very much present. In the words of Toni Morrison:

You know, they straightened out the Mississippi River in places, to make room for houses and livable acreage. Occasionally the river floods these places. ‘Floods’ is the word they use, but in fact it is not flooding; it is remembering. Remembering where it used to be. All water has a perfect memory and is forever trying to get back to where it was.76

Jota Mombaça, Ghost 7(1-7): French Historical Maladie, Frac des Pays de la Loire, Nantes. Documentation of work in progress, courtesy of the artist, 2024. [ID: Colour photograph taken from an elevated perspective in a room where a series of the muddy Ghosts are being aired on stands. The fabrics are pink and brown and partially decomposed after their time underwater. There is some kind of protective floor cover on the ground; it’s dark green and defiled by mud.]

Jota Mombaça, Ghost 7(1-7): French Historical Maladie, Frac des Pays de la Loire, Nantes. Documentation of work in progress, courtesy of the artist, 2024. [ID: Colour photograph taken from an elevated perspective in a room where a series of the muddy Ghosts are being aired on stands. The fabrics are pink and brown and partially decomposed after their time underwater. There is some kind of protective floor cover on the ground; it’s dark green and defiled by mud.]

////

Parts of this essay were previously developed for the public lectures “‘I’m the one with a sculpture at the bottom of the Ocmulgee River’: Amelia Groom on Beverly Buchanan,” at The New School, New York, in 2022, and “Wetlands (Notes on Beverly Buchanan’s submerged sculptures),” at Studium Generale, Gerrit Rietveld Academy, Amsterdam, in 2022. Sincere gratitude goes to Amalle Dublon, Alhena Katsof, Jort van der Laan, and Jorinde Seijdel for organising and hosting those events. Thank you also to M. Ty, Aidan Wall, Lytle Shaw, and Patricia de Vries for reading draft versions of the essay and offering thoughtful feedback, and to Jota Mombaça for the images.

////

This text was commissioned and published by Plot(ting), Gerrit Rietveld Academie Research Group Art & Spatial Praxis (LASP): plotting.rietveldsandberg.nl

1. Lytle Shaw, New Grounds for Dutch Landscape (Stockholm: OEI editör, 2021), 95.

2. Ibid., 77.

3. Ibid., 67.

4. Ibid., 68.

5. Joseph Noonan-Ganley, “Our Prop Mud,” Nero (21 April, 2021).

6. Huw Richards, “Elements leave their mark in Cardiff,” ESPN (13 February 2009).

7. Noonan-Ganley, “Our Prop Mud.”

8. Cited from public conversation with the author at “On Cyberfeminism in Australia” during The 24th Biennale of Sydney (panel, Ten Thousand Suns, Sydney, 28 February 2024).

9. Klaus Theweleit, Male Fantasies Volume 1: Women Floods Bodies History, trans. Stephen Conway in collaboration with Erica Carter and Chris Turner (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), 229.

10. Ibid., 245.

11. Ibid., 229.

12. Ibid., 229–230.

13. Ibid., 387.

14. Ibid., 389.

15. For more on metaphors of deluge and anti-Asian racism in Australia, see Jessica Zhan Mei Yu’s moving essay “All The Stain Is Tender: The Asian Deluge and White Australia,” The White Review (March 2021), https://www.thewhitereview.org/feature/all-the-stain-is-tender-the-asian-deluge-and-white-australia/

16. Theweleit, Male Fantasies Volume 1, 409.

17. Ibid.

18. Ibid., 387.

19. UChicago Division of the Humanities, “C. Riley Snorton, The Wild Man in the Green Swamp and Other Stories about Race in America,” YouTube, recorded 16 October 2021, published 6 November 2021, http://youtu.be/csOk-3KGVXk. Snorton’s forthcoming monograph, tentatively titled Mud: Ecologies of Racial Meaning, examines racial practices in relation to swamps.

20. Ursula K. Le Guin, “Being Taken For Granite” in Ursula K. Le Guin, The Wave in the Mind: Talks and Essays on The Writer, The Reader, And The Imagination (Boston, MA: Shambhala Publications, 2004), 8.

21. Ibid., 9.

22. Ibid., 8.

23. Ibid., 9.

24. Ibid.

25. Isabelle Fremeaux and Jay Jordan, We Are ‘Nature’ Defending Itself: Entangling Art, Activism and Autonomous Zones (London: Pluto Press, 2021), 48.

26. Ibid.

27. Ibid., 49.

28. Letter dated 11 July 1979, in Lucy Lippard’s personal archives.

29. Monique Allewaert, “Swamp Sublime: Ecologies of Resistance in the American Plantation Zone” in PMLA (March, 2008, Vol. 123, No. 2), 343. This article opens with Georgia’s sea islands, which Buchanan’s Marsh Ruins sit next to. The history and culture of these islands were important in Buchanan’s conception of the work.

30. Amelia Groom, Beverly Buchanan: Marsh Ruins (London: Afterall Books, 2021).

31. Elizabeth A. Sutton, Capitalism and Cartography in the Dutch Golden Age (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2015), 86.

Sutton points out that while Portuguese colonists in the New World tended to build settlements on land that was high and dry, the Dutch colonists chose to settle on low-lying marshy and coastal areas.

32. Walter Rodney, A History of the Guyanese Working People, 1881–1905 (Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press, 1981), 2.

33. Alette Fleischer, “The Beemster Polder: Conservative Invention and Holland’s Great Pleasure Garden,” in The Mindful Hand: Inquiry and Invention from the Late Renaissance to Early Industrialization, Lisa Roberts, Simon Schaffer, and Peter Dear, eds. (Amsterdam: Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen, 2007), 145.

34. Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker, The Many-Headed Hydra: Sailors, Slaves, Commoners, and the Hidden History of the Revolutionary Atlantic (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, Massachusetts, 2000), 44.

35. Vittoria Di Palma, Wasteland: A History (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2014), 99.

36. Ibid., 110.

37. Ibid., 111.

38. Judith A. Carney, Black Rice: The African Origins of Rice Cultivation in the Americas (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001).

39. Sylvia Wynter, Black Metamorphosis: New Natives in a New World, unpublished manuscript, no date, housed in The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York, 20.

40. Ibid., 19.

41. Sylvia Wynter, “Novel and History, Plot and Plantation,” in Savacou: A Journal of the Caribbean Artists Movement 5 (June 1971), 99.

42. Wynter, Black Metamorphosis, 19.

43. Ibid.

44. Ibid., 19–20.

45. See Rod Giblett, “Theology of Wet Lands: Tolkien and Beowulf on Marshes and Their Monsters,” in Green Letters: Studies in Ecocriticism 19, no. 2 (2015); and Rod Giblett, Postmodern Wetlands: Culture, History, Ecology (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1996).

46. See Lindsey Dillon, “Civilizing swamps in California: Formations of race, nature, and property in the nineteenth century U.S. West,” in EPF: Society and Space 40, no. 2 (2022), 258–275. Dillon looks as “the transformation of swamps into private property, solid ground, and homogeneous space” as an example of “settler ecologies” that “spatialized individualist and instrumental ways of relating to land, with significant ecological effects.” Ibid., 260.

47. Megan Kate Nelson, Trembling Earth: A Cultural History of the Okefenokee Swamp (Athens, GA: The University of Georgia Press, 2005), 4.

48. Emily O’Gorman, Wetlands in a Dry Land: More-Than-Human Histories of Australia’s Murray-Darling Basin (Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 2021), 11.

49. Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861; repr., ed. Nell Irvin Painter, London: Penguin Books, 2000), 126.

50. Willie Jamaal Wright, “The Morphology of Marronage,” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 110, no. 4 (2020), 7.

51. Ibid., 2.

52. Kathryn Benjamin Golden, “‘Armed in the Great Swamp’: Fear, Maroon Insurrection, and the Insurgent Ecology of the Great Dismal Swamp,” The Journal of African American History 106, no. 1 (Winter 2021), 10.

53. Jota Mombaça, “SIX QUESTIONS posed by Lauren Sorresso to Jota Mombaça on THE SINKING SHIP/PROSPERITY, a solo exhibition at KADIST San Francisco,” Kadist (2022).

54. Ibid.

55. Ibid.

56. Ibid.

57. The subtitle of this section of my essay, “sinking could be an elevation,” also comes from one of Mombaça’s poems, which the artist read on the occasion of THE SINKING SHIP/PROSPERITY Current 1: Conversation with Jota Mombaça and Darla Migan (lecture, Kadist, San Francisco, 14 November, 2022).

58. Mombaça, “SIX QUESTIONS.”

59. Instagram post caption from Jota Mombaça, @jotamombaca (27 November, 2023).

60. Wynter, Black Metamorphosis, 51.

61. Ibid., 52.

62. Ibid., 52–53.

63. Wynter, “Novel and History, Plot and Plantation,” 99.

64. Ibid., 100.

65. Wynter, Black Metamorphosis, 53.

66. Ibid., 48.

67. Wynter, “Novel and History, Plot and Plantation,” 99.

68. Wynter, Black Metamorphosis, 28.

69. Ibid., 51.

70. Wynter, “Novel and History, Plot and Plantation,” 99.

71. Édouard Glissant: One World in Relation, directed by Manthia Diawara (K’a Yéléma Productions, 2010).

72. Wynter, Black Metamorphosis, 53.

73. Ibid., 19.

74. O’Gorman, Wetlands in a Dry Land, 46–58.

75. Cited in Linebaugh and Rediker, The Many-Headed Hydra, 46. Emphasis added.

76. Toni Morrison, “The Site of Memory,” in Inventing the Truth: The Art and Craft of Memoir, ed. William Zinsser (second edition; Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1995), 98–99.

There’s No Beginning and There Is No End

“I refuse to acknowledge time.” With these outlandish words, Mariah Carey begins her memoir, The Meaning of Mariah Carey, published in 2020. “It is a waste of time to be fixated on time,” declares the elusive chanteuse. “Life has made me find my own way to be in this world. Why ruin the journey by watching the clock and the ticking away of years?” Instead of counting the minutes and years, Mariah wants to live life “moment to moment.” Indeed, moments are one of her favorite things. See “Mariah Carey Needs a Moment” on YouTube; it’s a much-loved ninety-second supercut from her 2010–11 infomercials on the Home Shopping Network, in which she sells fashion, perfume, and jewelry items while enthusing about having a “diamond moment,” a “retro moment,” a “bandana moment,” a “genius moment,” a “dual moment,” a “fragrant moment,” a “skin-tight moment,” a “transitional summer moment,” a “full-on evening moment,” a “fun cute remix moment,” and so on.

Mariah’s espousal of moments has inspired many, including Adam Farah-Saad (aka free.yard), a London-born and -based artist and dedicated Lamb whose work is often infused with MC’s language, lyrics, and iconography. (“Lambs” are what Mariah’s most devoted fans call themselves; collectively we are the “Lambily.”) Working across video, installation, and performance formats, Farah-Saad makes art with various things including poppers, friends, obsolete technologies like iPods and CDs, microdosing, wind chimes, personal memories and heartbreaks, fisheye lenses, cruising, lipsynching, and gourmet condiments. They have said that Mariah inspires them as an artist, “in terms of wanting to be really sincere and poetic in what I do and kind of not being afraid to even go a bit overboard with that.”3 Their solo exhibition at Camden Art Centre in 2021 was framed as a presentation of “peak momentations” from their life. The term “momentation,” they explain, refers to “a pronounced dwelling on the ephemeral—influenced by Mariah Carey’s queer disidentificatory theorisations of THE MOMENT.”

The word “moment” comes from the Latin “momentum,” meaning “movement, motion, alteration, change.” It’s a shifty word: “in a moment” means very soon, to be “of the moment” is to be very current, to “live for the moment” is to act without concern for the future or the past. Moments are often temporal intensities that stand apart from the time that surrounds them; when we say “I need a moment” or “I’m having a moment,” it’s about puncturing the flow of things by carving out a pocket of time outside of regulated time. Moments are very different from minutes; they are decidedly transient, unquantifiable, indivisible, and non-accumulative. They’re brief but capacious; you can’t section them out or add them up in any normative way. For Mariah, living a life of moments means living “Christmas to Christmas, celebration to celebration, festive moment to festive moment,” while simply ignoring the rest, and always refusing to acknowledge the banality and brutality of standardized, accumulative, linear time. As she writes, “Often time can be bleak, dahling, so why choose to live in it?”

LINK: READ THE FULL ESSAY AT E-FLUX

Update 27 March 2024 (Mimi’s anniversary): A French translation of the essay by Emmanuel Pierre published at The Master’s Clock.

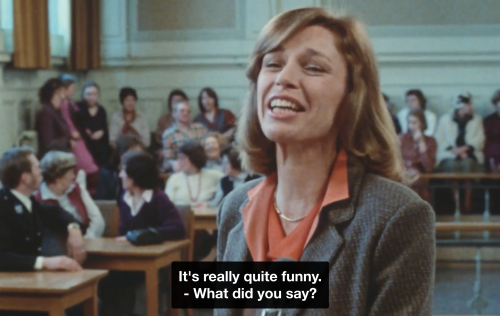

Lessons from Scheherazade

The tale has been told and retold many times: Scheherazade, the daughter of the sultan’s advisor, has volunteered to marry the sultan. The sultan is in the midst of a hysterical killing spree; he felt betrayed by his first wife, so he decided to kill her, and then marry a new woman every day, having each one beheaded after consummating the marriage on their first night together. Scheherazade has a plan. She marries the fearful and vengeful ruler, and then once she is in his chambers, she invites her sister Dunyazad in, ostensibly to say goodbye to her on her last night alive. Dunyazad then asks Scheherazade to tell her a story, and as she tells it, the sultan begins to listen in. Scheherazade is such a good storyteller that they all end up staying awake through the night. As day breaks, Scheherazade cuts the story short, so that the sultan will have to keep her alive in order to hear the end of the story later that night. She dutifully finishes the story when night falls, but then she immediately begins another story, an even better one, and again she stops the story at dawn, and survives for one more day, and so on . . .

The Arabian Nights or One Thousand and One Nights—as it is known in English—is a collection of Near and Middle Eastern stories that was compiled in Arabic over many centuries by many different writers, translators, scholars, and transmitters of oral histories, who drew from many different folkloric practices, including ancient and medieval Arabic, Greek, Indian, Jewish, Persian, Egyptian, Mesopotamian, and Turkish traditions. With multiple origins and many splintering versions, the Nights is a thoroughly decentralized and impure text which is made up of multiple texts and texts within texts—with layers of narration that move through and break open a plurality of genres, including romance, erotica, historical tales, tragedies, comedies, poems, riddles, jokes, proverbs, burlesques, murder mysteries, suspense thrillers, political satires, philosophical explanations, anatomical descriptions, and stories that could be described as early science fiction.

The commonality throughout the many versions is the framing narrative of Scheherazade, the woman who is telling these stories from within her own story. As a figure who is simultaneously a character in and the storyteller of the Nights, she manages to maintain a façade of deferential obedience to the sultan while also subverting the logic of hegemonic time from within—rerouting its linearity and interrupting the sense of inevitability that has been set by cruel precedent. As a masterful storyteller, Scheherazade knows how to fit stories onto and into other stories, and she knows how to break them off at just the right moment. By always terminating her stories before they’re finished, she can keep bringing in more stories, which means more nights—since the time of storytelling is exclusively nocturnal. And it is through this restructuring of continuity and discontinuity that she eventually manages to save her own life, as well as the lives of all the women who were to be raped and murdered after her, because her storytelling makes the sultan want to change his ways.

Through the art of fabulation, Scheherazade interrupts the temporality of the status quo, replacing the ruler’s repetitive and open-ended killing spree with her storytelling, which is also strategically repetitive and open-ended. Her situation is one of utter desperation: she has no time left, this is her last night alive, there is no futurity. But then, within the radical present tense of storytelling, she weaves continual interruption, extension, and deferral. Once she has suspended the sultan’s sequence of murders and elicited his curiosity, she’s able to perform a kind of temporal dilation, wherein the linearity of hegemonic time is pierced and stretched out, because she tells stories in which people tell stories in which people tell stories . . . The listening sultan is plunged into the time of the narration, which keeps opening up into more time, and each internal proliferation of time in the embedded stories gives the storyteller more time in the broader framing narrative that is her life.

أَلْفُ لَيْلَةٍ وَلَيْلَةٌ (One Thousand and One Nights) was first translated and repackaged for European audiences in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and ever since then the figure of Scheherazade has been burdened with the tedious and damaging projections of orientalism. In the introduction to her edited anthology Scheherazade’s Legacy: Arab and Arab American Women on Writing (2004), the Palestinian American scholar Susan Muaddi Darraj observes that the figure of Scheherazade was always revered in the East, but she “suffered terribly at the hands of translators […] An intelligent woman, schooled in literature, philosophy, and history, reduced to an erotic, shallow, sex-crazed body behind a veil—it happened many times, with many Arab and/or Eastern women, including Cleopatra, Khadijah, and Aisha.”[1] In spite of the west’s creepy and reductive warpings, though, Darraj writes that many contemporary Arab women writers have reclaimed the image of Scheherazade as someone who “wove a marvelous tapestry of tales” and “who saved a nation and healed its king.”[2]

In her book Stranger Magic: Charmed States & the Arabian Nights (2013), the feminist mythographer Marina Warner observes that throughout the Nights, Scheherazade’s tales gradually move “towards a politics of love and justice that opens the cruel Sultan’s eyes to another vision of humanity.”[3] Within her complex tapestry of composite and multiply enveloped stories, Scheherazade begins to weave threads of critique: with stories about subjugated women who are clever and courageous, she chips away at the sultan’s rationale for his hatred; and with stories about murderous tyrannical men who learn to pull themselves together and mend their ways, she establishes an alternative lineage of precedent. Storytelling is deployed as an ancient technique of consciousness raising, and by the end of the Nights, Scheherazade has succeeded in getting the sultan to stop killing, not only because he wants to keep hearing more stories, but also because he doesn’t want to kill any more.

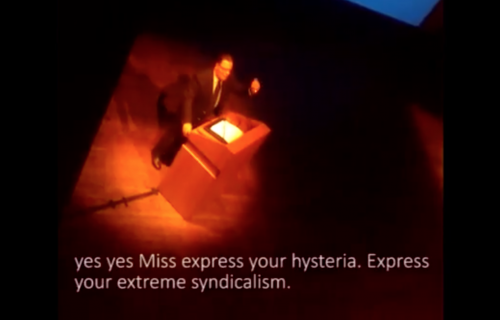

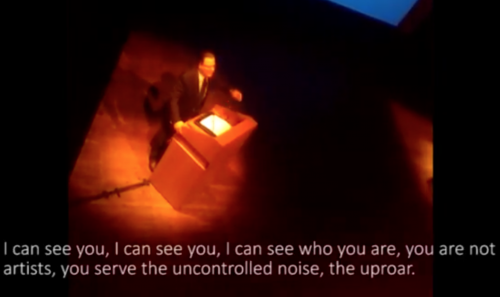

In some ways, Scheherazade’s approach aligns closely with the definition of parrhesia, or “speaking truth to power,” that was outlined by the philosopher Michel Foucault in a series of lectures given at the University of California, Berkeley in 1983.[4] Looking primarily at the context of ancient Greece, Foucault observed that the parrhesiastes, the one who speaks truth to power, “is always less powerful than the one with whom he speaks.”[5] Leaving aside for now Foucault’s exclusive use of male pronouns, the idea here is that parrhesia is critical speech which happens within an uneven power relation, and it is thus a dangerous activity which requires courage. The parrhesiastes is someone who speaks from a position of risk; in its most extreme form, Foucault says, “telling the truth takes place in the game of life or death.”[6]

This is certainly the case for Scheherazade; her situation is literally a matter of life or death. Closely related to the dimension of risk, in Foucault’s outline of parrhesia, is the dimension of duty. The parrhesiastes is someone who prioritizes their commitment to others above their own self-interest. In Scheherazade’s case, when she volunteers to marry the sultan, she forfeits her own security—and when her highly risky gamble pays off, she doesn’t just save her own life, she has acted from a sense of duty to others in order to end this man’s murderous rampage.

But Scheherazade’s practice of critique also diverges from Foucault’s outline of parrhesia in several ways—and these divergences can help us get to an expanded understanding of what political protest, critique, and activism can look like. While Foucault’s parrhesiastes is someone who chooses “criticism instead of flattery” when they speak truth to power, Scheherazade must deliver her criticism cloaked in flattery and subservience.[7] She does exactly what the sultan tells her to do, finishing the story from the previous night—just as he demands—when the next night comes around. She understands that it is only by playing with the sultan’s vanity, and maintaining his fantasy of control, that she is able to position him as a listener. While he thinks that she is obediently following his commands, her storytelling is actually making him embody the kind of listening that will lead him to challenge his own assumptions.

Foucault emphasizes “frankness” as part of his basic criteria for the Greek idea of parrhesia. His parrhesiastes is someone—someone male—who “makes it manifestly clear and obvious that what he says is his own opinion,” always “avoiding any kind of rhetorical form which would veil what he thinks.”[8] Scheherazade, meanwhile, is an artist of veils and indirection. As a woman who is married to a sultan who hates women, who kills with impunity, and who is planning to cut off her head in the morning, she becomes an oblique parrhesiastes, transmitting oral histories and gathering fabulatory tales while spinning them into a material means of survival, and of critique.

Some of the critique happens through the content of her stories—as when she introduces details that bear resemblance to the sultan and the situation that she is in with him—but her primary strategy is not about delivering a clear and direct political message that is designed to convince at the level of content. Rather, her polyphonic storytelling builds a space in which she can gradually shift the sultan’s perspective, and interrupt his myopic rage, by expanding his perceptual capacities. Through the masterful deployment of deferrals, detours, ellipses, cliffhangers, and embedded narratives, she clears more and more time for more and more voices, creating a situation of expansive compassion and mutual enjoyment.

“One can never go to the ruler in a direct way; in order to voice one’s opinion, one has to take an indirect way.”[9] This is the postcolonial feminist scholar and filmmaker Trinh T. Minh-ha, in conversation at a screening of her work in London in 1992. She is referring broadly to the situation of marginalized peoples caught in uneven power relations—but one could imagine that she is speaking specifically about Scheherazade, who understands the necessity and the potential power of indirect modes of address. In valorizing indirection from a feminist perspective, Trinh acknowledges:

there is always a danger, in assuming a tone and a position of indirection, that one may simply fall back into the habit of understating and of muting one’s voice as expected from women: We are, after all, supposed to abide by the rules of proper feminine speech and manner, never going at something too aggressively and too directly, often taking the back door, the discreet path to arrive at certain locations or to make certain points.[10]

However, while there is this danger, Trinh also insists here that attitudes of indirection “can be assumed submissively, strategically or creatively.”[11]

Indirection, then, can be understood as more than just a survivalist necessity for the subjugated; it’s also an approach that can bring its own poetic and epistemological possibilities. While the effect might frustrate audiences who are looking for a clear, convincing, and direct political message, strategies of indirection and opacity can ultimately work against processes of reductive appropriation, instrumentalization, commodification, and assimilation. In the context of late capitalism, Trinh argues, “it is important to work with indirection and understatement, if meaning is to grow with each viewer, and if the interstices of active re-inscription are to be kept alive.”[12]

At the start of her book Woman, Native, Other: Writing Postcoloniality and Feminism (1989), Trinh describes a nocturnal scene in an unnamed “remote village,” where people have gathered for a collective discussion. Rather than getting straight to the point, the participants in this discussion proceed through oblique and digressive paths, enacting a multiplicity of possible ways into and out of the discussion. “Never does one open the discussion by coming right to the heart of the matter,” Trinh writes. “For the heart of the matter is always somewhere else than where it is supposed to be. […] There is no catching, no pushing, no directing, no breaking through, no need for a linear progression which gives the comforting illusion that one knows where one goes.”[13] The nonlinearity of the indirect approach means that there is no preconceived beginning or ending; each speaker remains responsive to the situated context and allows things to emerge from it relationally.

As Trinh comments elsewhere, approaching the subject of one’s focus indirectly “allows oneself to get acquainted with the envelope, that is, all the elements that surround, situate or simply relate to it.”[14] An approach of direct opposition can treat the object of critique as something that is stable, neatly delineated, and external to oneself, whereas indirect approaches can allow for more nuanced understandings of the shifting relations and conditions surrounding the object—relations and conditions which include the position of the speaker. “It is in indirection and indirectness,” Trinh observes, “that I constantly find myself reflecting back on my own positions.”[15]

Foucault’s work on parrhesia has often fed into the familiar image of the activist as a heroic individual addressing a crowd with a bullhorn. When Semiotext(e) posthumously published his Berkeley lectures on parrhesia as a book called Fearless Speech (2001), for instance, they chose for the cover a black-and-white photograph of Foucault speaking through a megaphone at a protest on the streets of Paris in 1969—and similar images of the charismatic philosopher wielding a bullhorn tend to reappear whenever his work on parrhesia is revisited.[16] This is what “speaking truth to power” tends to look like in the popular imagination: there is an isolated individual, in public space, whose amplified voice delivers an uncompromising and direct message.

When the figure of the courageous parrhesiastes becomes one of fetishised heroism—and when incitements to ‘speak up’ in the face of power are universally applied—the uneven distribution of risk and access are overlooked. For the undocumented, risking arrest at a protest can mean risking deportation. For many others—including detained and imprisoned people, and many sick and disabled folk and their carers—physical presence at the site of the public protest might be impossible. In looking to the figure of Scheherazade as an oblique parrhesiastes, we can start to move beyond figurations of individualized heroism, and begin to think about other forms of “fearless speech” that do not lend themselves so easily to clearly delineated representational imagery.

Rather than speaking on the street, in broad daylight, as an individual with a mic, Scheherazade is a storyteller who works quietly and nocturnally, within a sphere of domesticity, while hanging out with her sister. Excluded from the realms of public discourse, she does not oppose the sultan as an individual facing an individual. In fact, she doesn’t directly address him at all; she and Dunyazad have triangulated things so that the sultan—the embodiment of absolute power—is no longer the primary audience. As he listens in on these two sisters, their transgressive solidarity must not be recognized as such by him. Their courageousness necessarily goes under the radar. Critique, in this setting, is not performed as the transferal of predetermined content from point A to point B. Rather, it’s something that is practised through the creation of a multisensory environment for opening up new times within time. It is enacted through the pleasures of telling and retelling; through practices of digression and deferral—practices which stay in the process, in the midst of things, and which are always to be continued.

“Lessons from Scheherazade: On the Art of Indirection” was published in the Sandberg Instituut’s 2022 graduation publication, which aims at thinking about works “in progress” and over time, to get away from the high-pressure ideas of finality and culmination at the art school graduation show. More from Our Polite Society and Sandberg.

[1] Susan Muaddi Darraj (ed), Scheherazade’s Legacy: Arab and Arab American Women on Writing, Praeger: Westport, Connecticut and London, 2004, p. 1-2.

[2] Darraj, Scheherazade’s Legacy, p. 3.

[3] Marina Warner, Stranger Magic: Charmed States & the Arabian Nights (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013) p. 10.

[4] Michel Foucault, “Discourse and Truth: the Problematization of Parrhesia” (lecture series, University of California, Berkeley, October–November 1983) https://foucault.info/parrhesia

[5] Foucault, “Discourse and Truth,” p. 18.

[6] Foucault, “Discourse and Truth,” p. 16.

[7] Foucault, “Discourse and Truth,” p. 20.

[8] Foucault, “Discourse and Truth,” p. 12. Foucault argues in his lectures that parrhesia depends not only on courageousness and duty but also on a degree of privilege: the parrhesiastes in Greek society must be able to speak freely as a citizen, so foreigners, children, the enslaved, and women, are generally excluded from the activity.

[9] Trinh T. Minh-ha, Cinema-Interval (Routledge: New York and London, 1999) p. 25.

[10] Trinh, Cinema-Interval p. 25.

[11] Trinh, Cinema-Interval p. 25.

[12] Trinh, Cinema-Interval p. 25.

[13] Trinh T. Minh-ha, Woman, Native, Other: Writing Postcoloniality and Feminism (Indiana University Press: Bloomington and Indianapolis, 1989), p. 1.

[14] Trinh, Cinema-Interval p. 34.

[15] Trinh, Cinema-Interval p. 34.

[16] See, for example, the promotional image for the 2016–2018 event series Fearless Speech at Hebbel am Ufer, Berlin: https://www.hebbel-am-ufer.de/en/archive/fearless-speech/

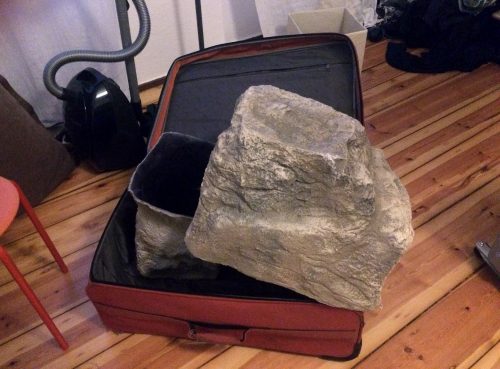

Beverly Buchanan: Marsh Ruins

Beverly Buchanan’s Marsh Ruins (1981) are large, solid mounds of cement and shell-based tabby concrete, yet their presence has always been elusive. Hiding in the tall grasses and brackish waters of the Marshes of Glynn, on the southeast coast of Georgia, the Marsh Ruins merge with their surroundings as they enact a curious and delicate tension between destruction and endurance. This volume offers an illustrated examination of Buchanan’s environmental sculpture, which exists in an ongoing state of ruination.

Amelia Groom illuminates Buchanan’s vision of sculptural ruination, and probes her remarkable work in terms of ideas of witnessing, documentation, landscape, and cultural memory. Existing in dialogue with land art and postminimalist sculpture, the Marsh Ruins are nevertheless unique refusals of art world classifications and systems of value. Making abstract use of concrete forms, Buchanan’s works embody their own stakes, from colonialism’s legacies of fracture and dislocation, to the workings of weather and time. In the words of her own mother, Buchanan had always “seen things” in rocks that others didn’t see.

Published by Afterall Books and MIT Press.

Support your local bookstore if you can! There is for instance bookshop.org for online shopping in US/UK. If in EU, I believe my favourite bookstore San Serriffe has copies of the book and is doing EU shipping.

Related talks / events / teaching:

29 January 2021 – Online lecture for Word & Image research group, University of Amsterdam.