‘Uncategorized’

Permanent Collection

When the Mona Lisa went to Washington, DC in 1963, it was the first time The Louvre had ever allowed her to travel abroad. The circumstances were exceptional: basically, André Malraux was smitten with Jacqueline Kennedy. She, America’s then-First Lady, and he, France’s then-Minister of Cultural Affairs, had first met in Paris in the spring of 1961. They spent a day together, visiting museums and speaking in French about art. Dazzled and eager to please, Malraux somehow made a spur-of-the-moment promise that da Vinci’s flimsy little picture would visit the US capital, IRL.

Surrounded by draped red velvet and guarded around the clock by US Marines, the Mona Lisa attracted ten thousand visitors to the National Gallery of Art on her first day there—and in the weeks that followed, and the museum had to extend their opening times to try to accommodate the crowds. In the midst of the media frenzy surrounding the event, Andy Warhol wondered why the French hadn’t just sent a copy. “No one would know the difference,” he remarked. And if no one knew the difference, what would the difference be? By sending a copy instead, The Louvre could allow everyone to experience a direct physical encounter with something that looked the same, while also keeping the original safely tucked away, preserved for posterity.

This was in fact the exact thinking that led to the closure of the Lascaux caves in the south of France, and the production of a facsimile nearby. Malraux took the Mona Lisa to Washington in January of 1963, and three months later his ministry was closing the Lascaux caves off from the public, in the name of preservation.

The paintings at Lascaux had survived for more than seventeen thousand years, but they threatened to disappear forever as soon as we got too close. As early as 1955, less than a decade after the site was opened to the public, contamination caused by the near-constant swarms of breathing humans was starting to show. The thought of accidently losing the pictures was evidently too much for us to bear—we had to lose them on purpose, by resealing the caves and replacing them with a likeness of our own making.

Plans for Lascaux II were drawn up, and a team of painters and sculptors began work on reproductions of several sections of the caves, with every contour and every mark replicated to the millimeter. The copy finally opened to the public in 1983, two hundred meters from the original site. Now nobody sees Lascaux I, but hundreds pass through the underground simulacra-sequel every day.

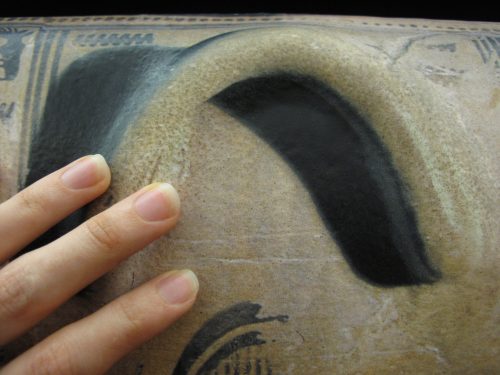

I’m deep underground, inside the Ōtsuka Museum of Art. Built into a hillside at Naruto, a small coastal town in southeast Japan, the museum has more than a thousand iconic works on permanent display. There’s da Vinci, Bosch, Dürer, Velázquez, Caravaggio, Delacroix, Turner, Renoir, Cézanne, van Gogh, Picasso, Dalí, Rothko—all the Western canon’s greatest hits. Even Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel frescos are here, lining the walls of a custom-built hall.

To “acquire” the works in this collection, a technical team prints photographs of them, in full scale, onto ceramic plates. They then fire the plates at 1,300 degrees centigrade and follow with some hand-painted touch-ups. According to the museum’s marketing material, these painted-photographed-printed-baked-painted pictures will then survive for several millennia. “While the original masterpieces cannot escape the damaging effects of today’s pollution, earthquakes and fire,” reads a statement from the museum director Ichiro Ōtsuka, “the ceramic reproductions can maintain their color and shape for over two thousand years.”1

The hundreds of millions of dollars that have gone into this enterprise came from the pharmaceutical company Ōtsuka Holdings—which is also behind the popular antipsychotic drug Aripiprazole, and the popular Japanese beverage Pocari Sweat. The museum’s full-time guide is a friendly faceless blue robot named artu-kun—“Mr. Art”—whose belly is branded with the Pocari Sweat logo. Part of his job is to remind visitors that it’s okay to touch the artworks here, since they’re indestructible objects.

Everything in this enormous underground museum is simultaneously anticipating and defying destruction. Has the apocalypse already happened, or are we still preparing for it? From inside the bunker, it’s impossible to tell. Looking at the ceramic reproductions today, I am looking at them in two thousand years—there’s no difference between now and then, because history is at a standstill.

I walk around the museum, photographing and touching the artworks. I stroke the cheeks of Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring, and I press my face against Klimt’s Kiss. But the closer I get, the further away they seem. Does it still count as touching if my touch is guaranteed to have no effect?

The novelty of touching the art soon wears away, because every surface is so neutralized. The artworks start to feel like one big piece of worn-out sandpaper—and the surface of time itself is flattened into a mythic, homogeneous continuity. This is what art worthy of preservation looked like to the Ōtsuka team at the end of the twentieth century, and—if everything goes according to plan—nothing is ever going to change.

In the 1990s, while the Ōtsuka Museum was amassing its collection of everlasting copies, Jean Baudrillard was decrying what he called “the Xerox degree of culture,” where “Nothing disappears, nothing must disappear.”2 With the Lascaux caves as his recurring example, Baudrillard questioned our increasing proclivity for preservation-by-substitution, where things that would otherwise be allowed to pass are forced into artificial longevity, via their simulacra.

Evoking current debates in France about doctors artificially keeping patients alive, even when ultimate life expectancy is unavoidably short, Baudrillard used the term acharnement thérapeutique or “therapeutic relentlessness.”3 This is an apt analogy for what happens at the Ōtsuka Museum of Art: a superimposition of relentless, compulsory vitality onto artworks and europhilic art historical narratives that might otherwise have very little life left in them.

Ōtsuka has even started to take this therapeutic relentlessness a step further, by embarking on forcible revivals of the already dead. The latest acquisition for the permanent collection is their first copy of a work of art that does not exist: a painting of sunflowers in a vase, by Vincent van Gogh, which was destroyed in Japan in 1945. Along with everything around it, the painting was turned to smoke and ash during a US air raid over Ashiya on August 5–6—around the same time as the first atomic bomb exploded over Hiroshima.

But according to the brightly colored ceramic plate now on show at Naruto—which was rendered from photographs that predate the picture’s incineration—World War II never happened. In fact, according to the art history that Ōtsuka is locking into place for the next two millennia, nothing will ever happen. This is a revised and idealized version of history, with all the ruptures covered up, and all of time’s contingencies tidily sealed off. In other words, it is a version of history without a real temporality.

Let’s imagine that these ceramic boards really do survive untarnished for the next two thousand years. What would a future alien visitor then find here, amongst the ruins? It’s a history of Western art, beginning with Ancient Greece and progressing in a dead-straight line through the centuries, before finally landing at Abstract Expressionism and American Pop Art: the grand apotheosis of a three-thousand-year-long narrative. Nothing after 1970 has yet received the Ōtsuka treatment.

Of course, the more expansive any attempt at a total comprehensive overview is, the more its inherent incompleteness will show through. At Ōtsuka the feeling is one of overwhelming excess—it’s the largest museum in Japan and seeing everything means walking for almost four kilometers—as well as alarming omission. For instance, there are hundreds and hundreds of works, but the female artists who have been invited into this grand narrative can be counted on one hand. Initially I thought this would begin to improve, at least a little, as I moved along Ōtsuka’s chronological progression of art from antiquity up to the 1960s—but I found that the only non-male artist who appears in the postwar era is Bridget Riley.

This is a version of art history with no sculpture, no video art, no performance or installation art, no ready-mades—only flat photographically reproduced paintings and some other things that are made to look like flat photographically reproduced paintings. A selection of medieval tapestries and Byzantine mosaics are included, as photographs fired onto ceramic boards—their textures completely flattened out. Stranger still are some Ancient Greek vases which have been photographed from all sides and printed as two-dimensional rectilinear planes, with shadows from the handles included as part of the image surface, indicating their former three-dimensionality. But although everything here depends on photographic technology, this is a history of art in which photographs have never featured as artworks in themselves. The camera is simply a vehicle that transfers images from surface to surface; it does not make its own images.

In Mr. Ōtsuka’s statement about the museum, he proudly announces that visitors can now finally “experience art museums of the world while being in Japan.” But if this is really about increased accessibility, we might wonder why the artworks that are selected for reproduction are already some of the most widely reproduced and accessible images of all time. The museum opened at the turn of the twenty-first century, by which point anybody with an internet connection anywhere in the world would be able to access any of these iconic images, sometimes with resolutions that reveal more detail than our naked eyes could ever see.

As a mode of reproduction, photography invites multiplicity, fragmentation, and circulation. Writing in the 1940s, Malraux observed that the photographic document can liberate the object from its context and hierarchical positioning, as well as from its physical volume and prescribed dimensions.4 But unlike Malraux’s “museum without walls”—and unlike Taschen books or Google Art Project—the Ōtsuka team returns volume, weight, and location-specificity to the mechanically reproduced work of art. They turn dematerialized images back into singular, heavy objects with fixed dimensions and spatial positions, so the images don’t travel to us—we have to travel to them.

If Ōtsuka’s ceramic board copies actually fulfill the promise of surviving untarnished until the year 4016, they will almost certainly outlive the originals they refer to. More than duplicates, they’re replacements. Their aim is to permanentize pictures and histories that are relatively fragile and transient.

When the Umbria and Marche earthquake struck central Italy in 1997, destroying much of the thirteenth-century frescoes in the Basilica of St. Francis in Assisi, the Ōtsuka team offered to lend their newly acquired photographic versions of the frescos to the Italians, for consultation during the restoration process. The original could then be rendered as a copy of its own copy—and every time its material veers away from what it was, consultation with the allegedly indestructible simulacra can bring it back into line.

There is a broader issue here, which is about finding ways to look at artworks without taming their dynamic and durational capacities. When art historians seek to pin down works of art to a single date of authorial inception, the temporal multiplicity of the work is denied. Likewise, when conservators imagine returning a work to the condition of the “artist’s original intentions,” they fight against the ongoing durations of art objects—objects which always accumulate marks of their historical and material realities.

The Tate Modern’s 2013 retrospective for Saloua Raouda Choucair included an abstract painting that was riddled with holes and had shards of glass sticking out of it, as a result of a bomb going off near the artist’s home during the Lebanese civil wars. She had decided to leave the canvas unrepaired, so it could continue to bear witness to the violence that it had endured. The ruptured abstract composition thus took on a direct indexical relation with the external world. The picture pointed not just to a moment of artistic creation in the past, but also to what it had been through since then—so its temporality extended beyond the initial instance of creative authorship.

But the Ōtsuka Museum of Art is founded on an attempt to deny the passage of time. There is no past here, since nothing passes away and all the scars of history can be covered up, and there is no futurity, since there is no space for contingency or chance. In this archive there is only the relentless, permanentized present, preempting any alternate future, replacing everything else with itself, enforcing more of the same forever.

Adorno observed that the words “museum” and “mausoleum” are “connected by more than phonetic association.” The German word “museal” (museum-like), he wrote, “describes objects to which the observer no longer has a vital relationship and which are in the process of dying.” Such objects go to the museum when they are ready to withdraw from life. In Adorno’s words, “They owe their preservation more to historical respect than to the needs of the present.”5 But is there not also potential for strategies of reactivation within the museum-mausoleum? Can’t we try to think about ways of setting its contents in motion, in accordance with the needs of the present?

As I was struggling to find my way out of the Ōtsuka Museum of Art, I started to become more aware of the seams that run through its pictures. Because the fired ceramic boards can only be produced up to a certain size, any larger surfaces have to be pieced together from separate plates. As a result, many of the pictures feature strange disjunctive grooves, which remind us of their base materiality.

The more I focus on these caesurae, the more the museum’s myth of solidity and clean continuity is disturbed. The hyper-durability of the baked ceramic plates comes with a compromise of surface interruption, and it is in the surface interruptions that we find evidence of the gaps that run through all versions of history—even and perhaps especially those that present themselves as watertight. Looking at the spaces in between the pieces—spaces we are not supposed to look at—I wonder what potentiality lies there. What leakages might pass through these openings? And how can the visible seams be taken up as an invitation to rearrange the contents of the archive?

Certainly, the Ōtsuka Museum of Art is a corporate vanity project, which presents its reactionary version of art history as something conclusive and unchanging. It fetishizes individual (white male) genius, perpetuates simplistic progress narratives, costs too much money, takes up too much space, and fails to properly deal with the temporality of the art that it cares for. But which of our major art institutions are exempt from such criticisms? In its excessive permanence and false totality, Ōtsuka is simply reproducing the problems encountered in contemporary museological, art historical, and preservation practices more generally. In this respect, the Ōtsuka Museum could also be considered the most elaborate work of institutional critique ever attempted.

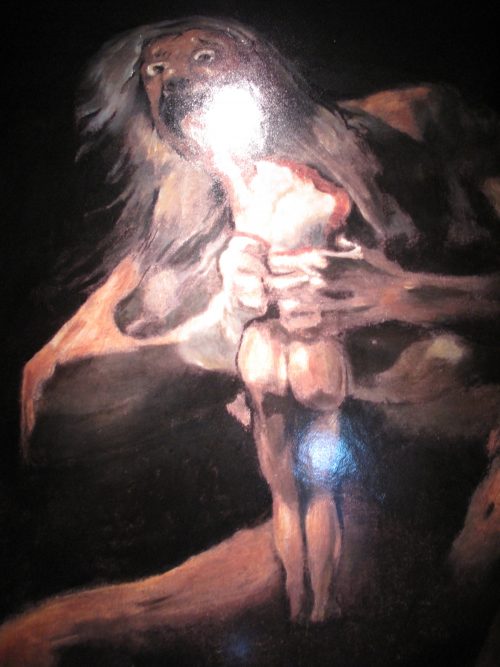

Still trying to find the exit, I stumble into a darkened room with reproductions of Goya’s Black Paintings, and I stop in front of Saturn Devouring His Son. It’s a truly appalling image: a naked, cowering old man with bulging eyes looking right back at us, and a half-eaten child clenched in his knuckly fists.

Saturn is the Romanization of Cronus, the Greek god of time whose image later morphed and amalgamated into the bearded, scythe-carrying old man known as Father Time. The myth of Cronus tells us that he had castrated and overthrown his own father, and so he was terrified that one of his children would one day do the same to him. To prevent this from happening he would consume them as soon as they left their mother’s womb.

The paranoid patriarch struggles to hold on to his position of power by desperately suppressing all futurity. He devours everything that could come after him, in a precautionary measure against the inevitability of change. This is an image of time that exists only as a perpetual, cannibalistic present, preemptively replacing any alternative with itself. There’s no real future in this version of time, since there is no indeterminacy, no contingency—only prediction and subsumption.

But Cronus’s struggle is ultimately futile—and somehow in Goya’s depiction he seems to know it. Rhea—who is Cronus’s wife, and sister—eventually makes a plan with Gaia, their mother. When Rhea gives birth to the sixth child, Zeus, the women hide the baby away—and they later force Cronus to disgorge the contents of his stomach, so that one by one the other infants are vomited back to life.

Here we are reminded that the future is not just something “in the distance” that we identify and move toward in a linear fashion; it can be unrealized potentiality that is already present, but suppressed. This futurity can be swallowed and withheld—but then it can be spewed up and redistributed. By intervening in Father Time’s system of control, it is the mothers in this myth who can restore the future’s messy indeterminacy.

An earlier version of this text is published in the book ‘La vie et la mort des œuvres d’art / The Life and Death of Works of Art’, edited by Christophe Lemaitre and published by Tombolo Presses, France, 2016 (in English with French translation).

Subsequently republished in e-flux journal #78, 2016 – see here.

Also republished, and translated into Dutch, for the book Pense-Bête, published by P/////AKT Amsterdam in April 2017 – see here.

all the objects

door mat, charm bracelet, stone, bone, strawberry, all my diamonds and clothes, honey, Windex, bells, golden petals, brand new white tee, dandelions, yellow cake, my favourite jeans, coffee, teddy bear, ice cream, ribbon, photos of us, her red dress, milkshake, music box, knife, donuts, a whole lot of gel and acrylic, camera, a broken rose, Asscher-cut pink and white engagement ring, gumdrops, sunflower, ketchup, glitter, Jimmy Choos, fries, my phone, medicine, Bacardi, mascara, mistletoe, tears, candles, gelato, black Cavalli shades, super glue, expensive lingerie, weed, cherry wine, two Lego blocks, meteorite, money, mini skirt, puppet,

As an exercise in list making, I started an inventory of objects found in Mariah Carey lyrics, using the archive at lyricsfreak.com.

I decided to only include objects mentioned in lyrics sung by Mariah herself, not by anyone else who features in her songs – so Nicki Minaj’s M&Ms and Jay-Z’s piece of paper were not included.

It was then supposed to be a cold, mindless process of extraction and accumulation, but I soon had to make choices; creating a list of objects meant coming up with some sort of provisional definition for what sort of thing an object is.

I needed boundaries. Should fire, rain and rainbows be listed as objects? They all appear several times in Mariah’s songs, but they seemed to lack sufficiently hard boundaries.

I thought of James Joyce listing all the objects in Leopold Bloom’s drawers, and I decided to only include things that could be found in a drawer. A drawer in Mariah Carey’s bedroom.

The contents of the drawer had to be detached, containable, not too big. So all the beds and all the doors were off the list, along with all the luxury cars, the roller coaster, the private jets and jacuzzis, the orange clouds, the winding road, the hills and plains, the stars, and the moon that appears in various phases in different songs.

Several plant specimens – dandelions, sunflower, mistletoe – made it onto the list, but I left out living things with central nervous systems, like butterflies, your body and my body.

Bodies and butterflies are, according to certain definitions and contexts, objects. We can also imagine them fitting into a drawer. So why exclude them?

If Mariah sung ‘touch my corpse’ rather than ‘touch my body’ I would have considered it an object – likewise if the butterflies were dead I could have pinned them down as objects. But I imagined that when the drawer was opened you and I would climb out, and all the butterflies would fly away… I couldn’t contain or predict the living bodies, so I didn’t include them.

Body parts (feet, forehead, waist, wings) were also left out, but tears were included since they are by definition expelled from, and therefore no longer part of, the body.

It’s still not entirely clear that tears should be listed as objects in this drawer. Tears tend not to be delineated material things for very long: they seep, vaporise, get wiped away, and generally aren’t stored in containers the way Windex, for instance, is.

Money is another contentious inclusion, since most money now has no physical manifestation, no hard objecthood.

Money and tears: formlessness, liquidity, absorption, evaporation, no bodies.

When caterpillars turn into butterflies their bodies break down into goo, before emerging with wings and completely reorganised brains and nervous systems. But despite the radical deformation and transformation, butterflies can carry memories from their pre-butterfly days: biologists have found that butterflies will avoid odours that they learned to associate with mild electric shocks when they were caterpillars. Where are the odour-memories kept?

The process of writing up the list of objects started as a process of establishing boundaries. The container was to be delineated before its contents were filled in, and all the contents seemed to be demarcated physical units with hard edges that push out the other.

But then, once the objects are put together the boundaries between them open up and the exclusionary operations can start to come undone. When I read the list of objects now, things are softened, gooey, sticky, floating, seeping, porous, coming together, becoming other.

Lists are both conjunctive and disjunctive; they shatter things to bits while they gather bits together. Ketchup mixes with glitter; diamonds and Lego blocks are covered in honey; Bacardi seeps into the mascara…

This is an excerpt from a text I wrote on ‘lists, inventories, enumerations, catalogues, itemisations, etc.’, as part of a guest-edited section for Oberon magazine. The section I edited also features contributions from Gianmaria Andreetta, Simonne Goran, Paul Thek, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, and others.

Indifference and Repetition

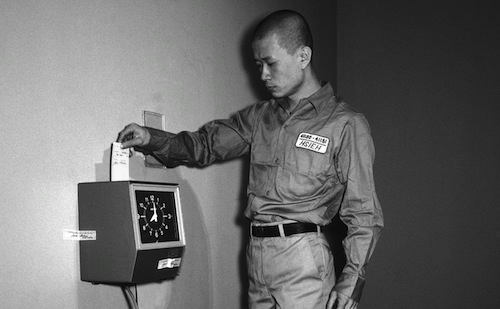

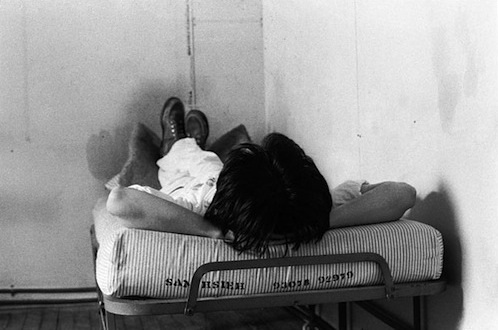

On September 30, 1978, Tehching Hsieh vowed to seal himself off in a cage inside his downtown New York studio, for one year. “I shall NOT converse, read, write, listen to the radio or watch television,” he wrote, “until I unseal myself on September 29, 1979.” A friend came daily to deliver food and remove waste. This became the first in a series of arduous yearlong performance works carried out by the artist.

For Time Clock Piece,Hsieh punched a worker’s time clock in his studio, every hour on the hour, day and night, from April 11, 1980 to April 11, 1981. He photographed himself each time he ‘clocked in’, and the thousands of resulting images were made into a time-lapse film, condensing 365 days into six minutes. For Outdoor Piece (1981-82), he vowed “I shall stay OUTDOORS for one year, never go inside. I shall not go into a building, subway, train, car, airplane, ship, cave, tent.” Rope Piece had him tied to the performance artist Linda Montano by an eight-foot rope, from the 4th of July 1983 to the 4th of July 1984.

A few months after completing that work, Hsieh announced his No Art performance piece, for which he would not make any art or engage with anything related to art for one year. His sixth and final durational performance work was his Thirteen Year Plan (1986-1999), during which time he declared he would make art without showing it to anyone. After that, he said he would “just go on in life.” I recently emailed him with some questions.

You started out as a painter. Why did you change to live art?

There was a gradual process from painting to performance. They are my cognition of art in different times.

For your first performance piece, you jumped out of a second story window and broke both your ankles. Are you some kind of masochist?

The work is destructive, it is a gesture of saying goodbye to painting, broken ankles were out of my prediction. I have no interest in masochism.

Was physical struggle part of what you were communicating through the long duration works, or just a side effect?

The struggle is there because of the situation in life and in art, but I don’t emphasise it, my work is not autobiographical.

After moving from Taiwan to New York as an undocumented immigrant, your first one-year performance saw you in voluntary solitary confinement, alone in a cage without speaking, reading or writing for twelve months. Was it boring in the cage?

Staying in a cage for a few days can be boring. Staying for 365 days, it is not the same anymore and you are brought to another state of living. You need to do intense thinking to survive through the year, otherwise you could lose your mind.

Is there a particular sort of freedom to be found in self-imposed constraint?

I didn’t need to deal with trifles in daily life when staying in the cage, I had freethinking, I lived thoroughly in art time and just passed time. The freedom found in the confinement is what one could find in a difficult situation, it is a way to understand life.

Your second one-year performance Time Clock Piece is a work of monumental monotony. The thing unfolds as one big etcetera – a self-perpetuating reiteration of the same, with nothing new accomplished or accumulated. ‘Clocking in’ is the start of the worker’s day: by isolating the act and repeating it on loop, you suspended commencement and stretched it out over a whole year. Was this a conscious defiance of the notion of progress?

Punching the time clock is itself the work, I didn’t need to produce anything in the context of industrialization. The 8760 times of punching in throughout the year is repetition, but in another way, each punch in is different from any other punch in, as time passes by.

The conditions of this work meant you couldn’t ever fall asleep or leave your studio for more than an hour at once, for a whole year. It’s as if you were making literal what the anarchist George Woodcock termed ‘the tyranny of the clock’ in 1944. Were you thinking at all about the mechanised regulation of time through the worker’s body that was brought about after industrialisation?

I thought of industrialisation but that is not what I wanted to say, I’m not a political artist. Although the time clock was invented to track an employee’s working time, I used it to record the whole passing of time, 24 hours a day for the duration of one year in life, like the nonstop beat of a heart. Life time and work time are included in this one year of art time.

Unable to legally work in the US, you dressed yourself in a worker’s uniform and enacted labour without production. Can we think of this as the reductio ad absurdum of industriousness – where deadpan diligence and punctuality in the extreme amount to an elaborate emblem of inefficacy?

To me this piece approaches time from a more philosophical perspective than that of industrialisation. Instead of the 9-5 working day, the time used in this piece is the time of life. The 24-hour punch in is necessary to record the continuity of time passing. I believe Sisyphus pushes the boulder 24 hours a day, not 9–5, and he does it forever.

You have often named Sisyphus as an early influence on your practice. How did the influence manifest?

I read Albert Camus’s The Myth of Sisyphus when I was 18, and I encountered its inspiration again and again in my early age. Rebellion, betrayal, crime, punishment, suffering and freedom form a cycle in my life experience, and are transformed in art.

The other influences you have named are Dostoevsky, Kafka and Nietzsche. These are all literary figures – why did your works take the form of performance? Did you need to be outside of language?

I’m not a person using words to create, I use art, but their thoughts inspire me, and I practice in life.

What is time?

Once a child asked me, “is future yesterday?” We all ask questions about time in different ways. Time is beyond my understanding, I only experience time by doing life.

Albert Einstein: “An hour sitting with a pretty girl on a park bench passes like a minute, but a minute sitting on a hot stove seems like an hour.” Was your own perception of time altered during the one-year performance works?

My works are like a mixture of sitting on a park bench with a girl and sitting on a hot stove. This was how I felt about the passing of time.

Laurie Anderson: “This is the time. And this is the record of the time.” What’s the difference?

For me the difference is between the experience of time and the documents of time. My performances happened in real time, documents are only the record.

Very few people saw your works as they were performed; most of us will only ever have the statements and the photographic/video evidence to go by. What is the relationship between lived time and remembered time in your work? Are the documents secondary traces of the works, or an extension of them, or something else entirely?

There is invisibility in the work, even if you came to the live performances. Documents are traces of the performances. Compared with the performances themselves, the documents are the tip of the iceberg. Audiences need to use their experience and imagination to explore the iceberg under the water.

Marina Abramović has referred to you as “a master.” Her manifesto states: “an artist should not make themselves into an idol.” Have you seen her in the Givenchy fashion campaign that just came out?

I don’t really pay attention to fashion and am not sure if that means she is an idol. As a powerful artist and a beautiful person, Marina is favoured by the times. Her ambition in art is much bigger than being an idol.

Having gained a level of notoriety in the New York artworld, your fifth and final one-year performance piece was a staged negation: you stated that starting July 1st 1985 you would “not do ART, not talk ART, not see ART, not read ART, not go to an ART gallery and ART museum for one year.” Instead you would “just do life.” What is the difference between art and life?

All my works are about doing life and passing time. Doing nothing, just passing time and thinking were my mentality and I turned it into the practice of my art and life.

After this abstention from anything art-related (paradoxically carried out as art), you announced a thirteen-year plan, to commence on your 36th birthday in 1986 and continue until your 49th birthday. Your statement read “I will make ART during this time. I will not show it PUBLICALLY.” Why this resistance to being public?

After the No Art piece it seemed contradictory to go back to doing art publicly. I had to do art underground for a longer period of time, which was the last thirteen years of the millennium.

Is art without a public still art?

Art cannot exist without public, but the public could be in the future – I published the work after thirteen years.

You made such radical work, but operated so quietly. Until very recently, you were excluded from all the standard surveys of performance and body art – and then in 2009 MoMA and the Guggenheim Museum in New York both showed your work, and Adrian Heathfield’s huge monograph Out of Now was published, and there was a resurgence of interest. Why did it take so long for people to look at what you had done in the 70s and 80s?

There are reasons not in my control. My work is done in my studio or in the streets, outside the system of the art world. Most of my work was done when I was an illegal immigrant with less publicity, and the work itself is not easy to categorise. Also it is to do with my personality, but I feel comfortable with this slow and durational recognition.

You have stated that you stopped making art because you ran out of ideas. Did you say everything you wanted to say with the six completed works?

My art is not finished, I just don’t do art anymore.

Now you are “just doing life.” Will you ever make art again?

Not doing art anymore is an exit for me. Art or life, to me the quality is not much different, without the form of art, still, life is life sentence, life is passing time, life is freethinking.

This interview was published in Das Superpaper #26 March 2013

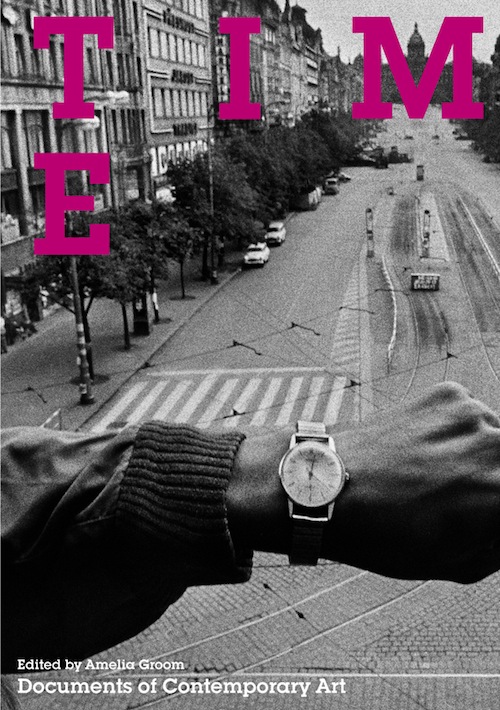

Time Pieces

Time pieces and pieces of time, time pieced together, time torn to pieces. As part of ‘Thinking Together: The Politics of Time’ at the 2015 MaerzMusik Festival for Time Issues (Haus der Berliner Festspiele, Berlin), I am giving a lecture on temporal porosities and hosting a series of seminars and presentations from guests including Sven Lütticken, Patricia Reed, Mark von Schlegell and Soda_Jerk. The conference begins with the full solar eclipse on March 20 at 09:38:42. The full program, with further details on Time Pieces, can be found here.

.

.

TIME

.

Artists surveyed include: Marina Abramović // Doug Aitken // Francis Alÿs // Matthew Buckingham // Janet Cardiff // Paul Chan // Jeanette Christensen // Moyra Davey // Dexter Sinister // Olafur Eliasson // Bea Fremderman // Antony Gormley // Douglas Gordon // Tehching Hsieh // Toril Johannessen // On Kawara // Joachim Koester // Lee Ufan // Christian Marclay // nova Milne // Trevor Paglen // Philippe Parreno // Katie Paterson // Raqs Media Collective // Sylvia Sleigh // Simon Starling.// Michael Stevenson // Hito Steyerl // Hiroshi Sugimoto // Time/Bank // Agnès Varda

“Questions of temporality currently preoccupy the world of artistic creation, as well as its history. Discussions about ‘the contemporary’ reveal the wealth of ideas that have replaced the architecture of continuity and teleology that once supported the notion of modernity. Heterochronicity and anachrony now replace chronology as the temporal models most suited to the understanding of works of art. This anthology brings together a host of interesting reflections by artists, critics, historians and philosophers on a topic that proves inexhaustible. These authors argue that representation itself proves incapable of grasping the elusive nature of time, since temporal instability is the hallmark of language.”

– Keith Moxey, Barbara Novak Professor of Art History, Barnard College, Columbia University

“Theorizing time is itself a temporal and historical activity. Combing a focus on recent writing with glimpses of the longue durée of time-theory, this anthology presents us with a constellation that is far from frozen in time. Its elements interact and enter into new relations each time the volume is consulted. You can’t step into the same anthology twice.”

– Sven Lütticken, Lecturer on Visual Arts and Programme Director, VAMA, University of Amsterdam

Some reviews of the book can be found here.