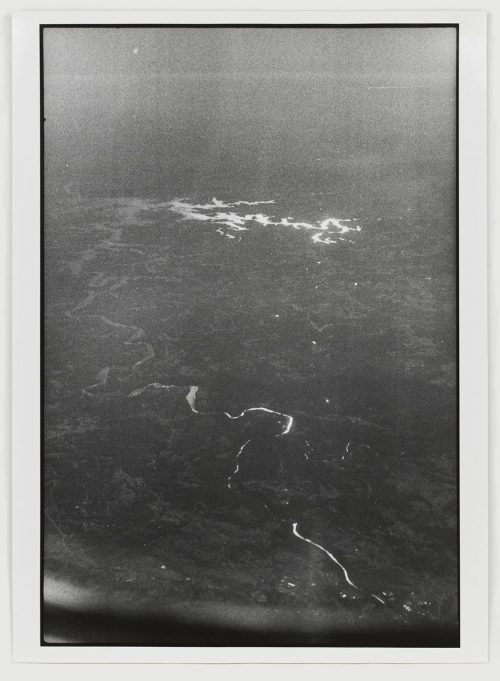

A river, seen from above. Silvery with sunlight, it bends and scatters through a landscape that recedes into a grainy haze. The picture is at once lush and imperfect, contaminated as it is by its own production; as shine bounces unevenly off the water, the light also arrives in reflective streaks on the windowpane that separates the photographer from the scene.

This image is part of Zoe Leonard’s Aerials (1986–89), an early series of black-and-white shots where the artist pointed her camera down from the windows of airplanes toward clouds, natural terrains, cityscapes, farmlands, and bodies of water. As is often the case with Leonard’s photographs, the edges of the negative are left visible in the print, affirming the materiality of analogue photo development and tying the image back to the framing device of the camera. In Untitled Aerial (1988/2008), part of the airplane’s window frame has also made it into the pictorial frame, with the blurred curve at the bottom reminding us of the photographer’s physical presence behind the camera.

The picture doesn’t come from a disembodied nowhere; it’s a view from above which remembers its own situated perspective. Leonard’s work has often returned to the fact that looking at involves looking from; her immersive camera obscura installations from more recent years, for instance, have invited viewers to look while also looking at the conditions of looking.

Untitled Aerial has two dates; the first, 1988, indicates when the photograph was taken, the second, 2008, is when the print was made. Back in ’88, Leonard was increasingly involved in queer activist work, as a member of ACT UP (the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) in New York. Her close friend David Wojnarowicz had by this time been diagnosed with AIDS; the illness had already taken his artistic mentor and former lover Peter Hujar, and many in their community were sick, dying, traumatised, mourning.

In her biography of Wojnarowicz, Fire in the Belly, Cynthia Carr recounts Leonard’s memory of inviting Wojnarowicz around to her apartment one day, to show him some work-in-progress from the Aerials series. “I had stacks and stacks of prints all over the floor, and he was so kind,” Leonard remembered. “I confided in him about this conflict I was having as an artist about the intensity of the activist work and the harshness of the reality of the crisis and—I was photographing clouds.” His response, she recalled, was to say, “Zoe, these are so beautiful, and that’s what we’re fighting for. We’re being angry and complaining because we have to, but where we want to go is back to beauty. If you let go of that, we don’t have anywhere to go.”

Writing in the late ’80s about his own work with ACT UP, the critic Douglas Crimp called for an expanded sense of militancy—one that would retain space for mourning and acknowledge a whole range of conflicting emotional states: “frustration, anger, rage, and outrage, anxiety, fear and terror, shame and guilt, sadness and despair” along with “deadening numbness or constant depression”. Rather than dismiss mournful feelings as indulgent or politically meaningless (as in the slogan Don’t mourn, organize!), Crimp insisted that trauma will always move through many different forms, and that the militancy should be able to remember the loss that it arose from.

Across Leonard’s varied practice, rage and mourning register alongside and out of the quietly studious and the visually pleasurable. Her silver river––which Fred Moten sees as “taking topological advantage of the opportunity to get away from itself for a little while”––is displayed in A FIRE IN MY BELLY opposite the exhibition’s eponymous work, an unfinished film from 1986–87 by Leonard’s beloved, lost, and remembered friend David Wojnarowicz.

This text was commissioned for the free magazine accompanying the exhibition A FIRE IN MY BELLY at Julia Stoschek Collection Berlin (on show February 6 – December 12, 2021). Here’s a PDF which includes the German translation.

Fred Moten, “Photopos: film, book, archive, music, sculpture” in Zoe Leonard: Survey (Prestel, 2018)

Douglas Crimp, “Mourning and Militancy” in October (Vol. 51, 1989)