PART ONE: ‘SHE IS CAPABLE OF COMMUNICATION, BUT NO LONGER SEES THE SENSE OF IT’

There are many different threads of silence woven through Marleen Gorris’s De Stilte rond Christine M. (1982), a “feminist thriller” which was the Dutch writer-director’s first film.[1] There’s silent obedience, but there’s also silence as a technique of interruption, and silence as a wilful refusal. There’s the silence of complicity within an unjust system, but there’s also the silence that is the condition of listening. There are oppressive and exclusionary silences that are imposed from above, and there are silences of attention, protection, intimacy and solidarity.

Released in English as A Question of Silence, the film tells the story of three middle-aged white women, strangers to each other, who brutally murder a male shopkeeper. They’re all browsing in a clothing boutique in central Amsterdam, when one of them is caught shoplifting. As she is confronted by the shopkeeper, the others silently join her and assemble around him, with a solemn sense of ritual purpose. Without exchanging any words, the three women begin their assault, beating the man to death with whatever is at hand: mannequin, shopping trolley, coat hanger, shards of a broken glass display unit, stiletto heels. The attack is hyperbolic in its brutality, but the film keeps all the gore out-of-shot: while the man is on the floor, the camera remains at the height of the women who tower over him. The live soundtrack is also muted under a cheesy ‘thriller music’ score, adding to the deliberate indirectness of the depiction, so the event is planted in a separated, almost allegorical realm.

The murder has already happened when the film begins, and the women are all taken into custody in the opening scenes. They make no attempt to resist the arrest or deny their involvement, but during the trial and in the lead-up to it, they refuse to speak to anyone about the circumstances of the crime. With much of the film being built out of flashbacks, we gradually learn about the lives of these women. The shoplifter Christine Molenaar – the ‘Christine M.’ of the film’s Dutch title – was a housewife with three noisy children. Sometime before the killing, she had given up speaking. Her husband comments that she “never had much to say”, but also that he thought she should have kept the children more quiet, so that he could relax when he got home from work, especially considering that she “didn’t have anything to do all day” anyway.

Then there’s Annie Jongman, a divorcee who lived with her cat and served tables in a café in the Jordaan, which was then a working-class suburb of Amsterdam. In contrast with Christine’s silence, Annie is disarmingly boisterous, with laughter never far from the surface. But while Christine’s homelife is depicted as relentlessly loud, Annie’s is uncomfortably quiet, with haunting memories of her former marriage flooding in once she finds herself alone in silence. The third woman involved is Andrea Brouwer, who worked as an executive secretary in an all-male firm, where her high level of competency only exacerbated the patronising contempt that she was up against. In an office meeting, we witness how her voice immediately produces impatience. Her boss interjects with, “Could you be brief?” as soon as she speaks, but then, predictably enough, when one of the men repeats what she just said, as if it was his own contribution, there are suddenly receptive ears for the idea.[2]

In the beginning, the women are all isolated in their varying conditions of silence – but the silence gradually becomes more collective, and more like an active practice. It spreads from Christine out to Annie and Andrea, who join in a silent recognition, which is also a recognition of silence. Through the fragmentary flashbacks to the scene of the crime, we eventually learn that the silence also reached four other women who happened to be in the shop at the time. These unnamed strangers did not participate in the attack, but they witnessed it, in attentive silence, and none of them reported what they saw. No words were exchanged between any of the women, but somehow a silent pact was formed, where silence would also become a means of protection; the ones who committed the crime will say nothing about the ones who saw them do it, and the ones who saw them do it will keep quiet about what they saw.

While the three killers are awaiting their trial, a court-appointed psychiatrist named Dr. Janine van den Bos is tasked with producing psychological reports on them. She tries to conduct interviews, but struggles to make progress. Annie is overly loquacious, going constantly off-topic, while Christine remains inscrutably withdrawn. Andrea, meanwhile, treats language as a site of play, where her words can flow as easily as Annie’s, but be as opaque and disorienting as Christine’s silence. Dr. van den Bos keeps showing up with her tape recorder, but she’s met only with silence, distraction, contradiction and obfuscation. Language isn’t working the way she wants it to; it’s either missing, or it’s misleading.

The film initially presents Dr. van den Bos as a comfortably middle-class woman who has ‘made it’ in a man’s world. She’s called upon to give her expert opinion within the judicial system; she speaks and is heard, or so it seems. But through her encounters with these women, she comes to realise that even she only ‘has a voice’ when she says what the men around her want to hear. By the end of the film, when her psychological assessments deviate from the court’s expectations, it becomes very clear that as soon as Dr. van den Bos goes off-script, all the old techniques of patriarchal silencing immediately come back into effect: she’s ignored, dismissed as incapable of objectivity, ridiculed for being concerned with trivialities, spoken over, and shouted down – or she has words put in her mouth, which is another way of ensuring that what she is actually saying goes unheard.

The force of collective silence gradually reaches the psychiatrist, as she comes to appreciate just how dysfunctional verbal language can be – and how much can be communicated without it. At one point in the film, she’s up in the middle of the night, remembering her unproductive interviews with the women. A rapid montage builds up, with repeated shots of Dr. van den Bos turning her head away from the camera, interspersed with flashbacks of the other women also turning away, so we see the backs of their heads, one after another. The hallucinatory editing brings their bodies into alignment, via this simple gesture of withdrawal. Far from being a withdrawal into apathy or pure negation, though, turning away will turn out to give rise to a whole new set of relations. The film’s final shot is Dr. van den Bos turning away from her lawyer husband, in order to face the group of women who were the silent bystanders at the scene of the murder. The shot freezes, and the credits roll over her face, which shows a sort of mesmerised silent acknowledgement, where her reorientation has opened up another world of possibility.

*

A Question of Silence has always been a divisive film. A report on its reception in the UK – by Jane Root from the feminist distributor Cinema of Women – relates how a Pizza Hut restaurant next to a cinema where the film was showing ended up full, night after night, of couples in heated arguments about what they had just seen.[3] As far as the critical reception went, there were some very positive responses, and then there was a lot of male hysteria. Writing for The Observer, Philip French called the film “inherently stupid” and “the unacceptable face of feminism”. Stanley Kauffman for The New Republic: “an atrocity”, “vicious”, “vile” and “entirely loathsome”. Milton Schulman for The Standard: “genocide is a comparatively modest moral device compared to the ultimate logic of this film’s message”. John Coleman for the New Statesman: it “tries to catch my gender in a Catch-22. To hell with it.” [4]

According to Marleen Gorris, the film was most deeply misconstrued within the Dutch context. “I was accused of depicting all this horrific violence,” she remembers. “There were these outraged descriptions of blood being splattered everywhere––when in reality there’s not one drop of blood shown in the film! All of that was put there by the viewer, so it was really a testament to the power of suggestion.”[5]

Meanwhile, user reviews on IMDB show that the film continues to produce confused vitriol. Among many favourable responses, there are some with titles like Insulting and Annoying and Dangerous propaganda from ill minded feminists. “The movie doesn’t even try to justify itself, or to present the subject from a male’s point of view,” one bemoans. “The film still needs work,” declares another. “You don’t excuse a criminal instantly because they were supposedly oppressed.” Again and again, claims that the murderers would be “proven right” or “instantly excused” are flagged as implausible and morally reprehensible.

What these unhappy viewers consistently miss is the fact the women in the film make absolutely no attempt to defend the violent crime. On the contrary, when the trial comes around, Dr. van den Bos actually refuses to diagnose the mental health of the murderers in a way that would imply any diminished responsibility. The male judge and public prosecutor try to convince her to designate legal insanity to the defendants, and thereby minimise the sentencing, but she is adamant that “the three women are completely sound of mind.” When the judge and prosecutor attempt to turn to Christine’s silence as proof of some mental incapacity, the psychiatrist informs them that the silence is in fact a choice she has made, that “she is capable of communication, but no longer sees the sense of it.”

With ‘madness’ being constructed as a non-insurrectionary category, the authorities want to dismiss the crime as a hysterical outbreak – one that was wholly irrational and essentially meaningless. But Dr. van den Bos has moved towards what could be characterised as an anti-psychiatry position, where the pathologised behaviour of the individual is inseparable from the oppressive structures of their society. Christine’s silence begins from her realisation that, as Annie puts it, “nobody is listening.” In refusing to grant the diagnosis that the court is trying to impose, Dr. van den Bos wants to listen more carefully to the silence; and to acknowledge that the women’s experiences of it have been culturally, politically, and historically determined.

The history of silence under patriarchy is of course long and multifaceted. One brilliant partial account of it can be found in Anne Carson’s essay The Gender of Sound, where she reads Ancient Greek sources alongside some more recent anecdotal and literary materials, and traces a continuing attachment in patriarchal cultures to the masculine-designated virtues of self-control and self-containment.[6] Carson argues that women (and whoever else is outside the exclusionary category of ideal masculinity––in the Ancient Greek context, she names “catamites, eunuchs and androgynes”) are associated again and again with disorder and verbal incontinence. Woman is “that creature who puts the inside on the outside,” Carson finds. “By projections and leakages of all kinds––somatic, vocal, emotional, sexual––females expose or expend what should be kept in.” They are like “leaky vessels” who need to be shut up––as per Sophocles’ dictum that “silence is the kosmos [good order] of women.”

The imposition of silence has obviously been indispensable in keeping huge portions of humanity away from public life and out of the history books. At the same time, something else that Gorris’s film understands is that if we only associate silence with powerlessness, isolation, inaction and irrelevance, we disregard the many expressive practices that have long subsisted within the absences that run through the historical record. As Adrienne Rich puts it in her poem ‘Cartographies of Silence’ (1975):

Silence can be a plan

rigorously executed

the blueprint to a life

It is a presence

it has a history a form

Do not confuse it

with any kind of absence

Power doesn’t only impose silence on its subjects; it also imposes discourse – and Gorris’s film shows that within the state’s psychological-judicial discursive regimes, there can be disruptive agency in silence. In a later essay called Variations on the Right to Remain Silent, Anne Carson looks to Joan of Arc, as she is forced to speak, during the inquisitions that led to her death sentence in 1431. Carson finds the voice-hearing, cross-dressing, illiterate peasant girl warrior surrounded by relentlessly prodding and coercive authority figures, all demanding “a conventional narrative that would be susceptible to conventional disproof”. But Joan of Arc responds to their questions with statements like “That does not touch your process”, “I knew that well enough once but I forget”, and “Ask me next Saturday”. Where her words carry silences, they mark a rejection of the demands for total transparency and translatability; and this is what Carson identifies as Joan of Arc’s “rage against cliché” – her refusal to maintain the status quo by regurgitating its inherited grammars.[7]

PART TWO: ‘SERVING THE UNCONTROLLED NOISE’

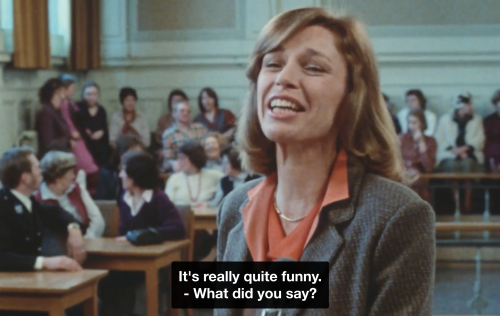

The most memorable scene in A Question of Silence comes near the end of the film, when the women are on trial. They have been watching the court proceedings in silence, seemingly bored and disengaged, occasionally showing signs of mild amusement. During his exchange with Dr. van den Bos, the obnoxious and increasingly incensed prosecutor insists that the genders of the murderers and their victim are irrelevant – that it would make no difference whatsoever if it had been three men who had killed a female shopkeeper. And then it begins: this dubious call to neutral reversibility suddenly sets off an eruption of laughter, starting with one of the women on trial, before spreading to all the other women in the courtroom, eventually reaching Dr. van den Bos herself.

As the laughter takes hold, things start to get out of hand. Dr. van den Bos tries to explain to the baffled and indignant judge that “it’s really quite funny––”, but she can’t get the words out properly, and in any case the room has become so loud that he can’t hear what she’s saying. The women on trial are eventually led out of the court, in joyous collective mirth, as the other women walk out together voluntarily, leaving the unamused men to continue with the proceedings on their own. “The case will continue in the absence of the defendants,” the judge announces, redundantly.

Laughter, here, is not something that exists alongside or in addition to words; it’s something that causes a total breakdown in their fundamental function. And while it begins in this scene in response to what has been said, it soon becomes the sort of laughter that leaves its subject behind, as laughter itself turns out to be the funniest thing. There’s a passage in one of Kafka’s letters that always cracks me up, where he describes a time when he was overcome by laughter while his boss was giving a dreary official speech. At first, Kafka laughs appropriately at the occasional little jokes in the speech, but then he laughs too much at them, and eventually he finds himself laughing “not only at the current jokes, but at those of the past and the future and the whole lot together”. Ha. Laughter arrives as an affront to rationalisation; it disorders chronology, undoes causal relations, and overrides explanation. As Kafka recounts, “I produced innumerable excuses for my behaviour, all of which might have been very convincing had not the renewed outbursts of laughter rendered them completely unintelligible.”[8]

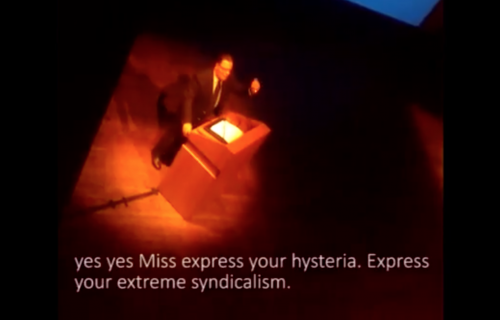

In 2014, the Greek artist-activist collective Mavili deployed laughter as a deliberately counter-linguistic tool, in a political intervention they planned at an EU conference in Athens called Financing Creativity.[9] The conference was supposed to address future models for cultural policy, but the role of culture was understood exclusively through the logics of entrepreneurship and economic growth, and no artists were invited as speakers. In response, the Mavili Collective called for artists from different fields to attend the proceedings and participate in a group action where their discontent would be given the form of collectively embodied and infectiously dispersed laughter.

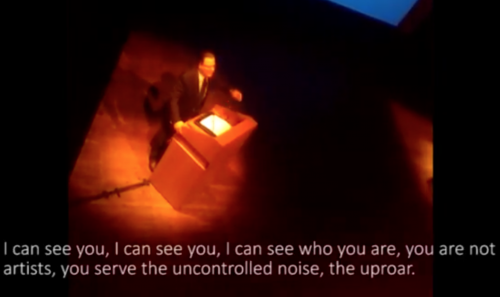

In grainy documentation from the conference, which Mavili posted on YouTube, the then Minister of Culture is giving his opening speech on the auditorium stage.[10] As he is pompously emphasising the importance of commercial competition between nations, he is interrupted by an outburst of laughter from audience members. He tries to continue, but disorder is unleashed. With more than a tinge of panic, he launches into an aggressive and highly revealing tirade, calling the laughing members of his audience “syndicalists” and “irresponsible cowards”. “Have the bravery of public speech”, he implores, “take the floor if you dare, face me directly and don’t hide behind the crowd.” But the collectivising and decentralising force of laughter continues. “I do a political act, what you do is uproar,” the man shouts, “you are not artists, you serve the uncontrolled noise!”

This “uncontrolled noise” is, of course, precisely the point. As with the affectively contagious eruption of laughter at the end of A Question of Silence, the assertion of laughter at the conference affirms that when language operates in a closed system that only reproduces its own terms, the political value of an expression can lie not in its semantic content, but in its capacity to interrupt the system’s conditions of exchange. Judith Butler argued as much in a recent lecture, where they posited that laughter’s critical potential lies precisely in its existence “beyond the spheres of communication and control”. As an involuntary bodily expression whose aim is not to impart a pre-determined idea, laughter, Butler suggested, can function as a mode of “extra-parliamentary political eruption and disruption”, where the loss of control has “expressive value and meaning that is quite separate from what the deliberate ‘I’ has to say.”[11]

Writing about A Question of Silence for Artforum in 1983, the artist Barbara Kruger described the laughter at the end as “a flood of ticklish escapes from the sombre rigor of ‘reason’,” noting that at each screening of the film that she attended in New York, “this infectious rupture spread to the theatre audience, producing a moment of stunning solidarity.”[12] From positions of domination based on operations of containment and control, the arrival of this kind of laughter is obviously deeply worrying. In her essay The Value of Laughter (1905), a 24-year-old Virginia Woolf observed that all the pompous conventions of masculine authority “dread nothing so much as the flash of laughter which, like lightning, shrivels them up and leaves the bones bare.”[13] This dread understands the way that laughter can cut through pretensions, leaving their absurdities and fragilities exposed. It also understands that laughter can be a contaminating force, and that part of its subversive potential lies in its capacity to produce spontaneous collectivities.

It makes sense, then, that the cackle has been such an indispensable characteristic of the witch as she is popularly feared; as a figure of transgression and scary excess, her capacity for flight and her proclivity for laughter are both signs of her non-containment. Another feminist writer of laughter is Hélène Cixous, whose witchy essay The Laugh of Medusa (1975) is bursting with the vocabularies of volcanic eruption. As the long-excised ‘feminine writing’ breaks through, Cixous tells us, “it brings about an upheaval of the old proper crust, carrier of masculine investments.”[14] In her reading, the powers that have driven women out from history, and from writing, have also worked to separate them from each other, and from their own bodies. The entry of l’écriture féminine would thus establish completely new languages, and new embodiments, through collectivising somatic forces like laughter – or what Cixous terms “the rhythm that laughs you.”

When Cixous promises that this explosion onto the scene of language will “blow up the law to break up the ‘truth’ with laughter,” she could be describing the courtroom chaos that ensues with the outbreak of laughter in A Question of Silence. Throughout the essay, though, Cixous opposes the explosive force of laughter to the condition of silence, which she characterises only as “the snare” that women “should break out of”, so that they can finally arrive into a shared language. This is quite different from Gorris’s richly nuanced treatment of silence, where it can signal subjugation, but it can also be a space of rage, refuge, and intimacy. If we imagine her film’s depictions of silence and laughter with a Venn diagram, the area of overlap is the juiciest bit. The silence and the laughter are both gorgeously defiant, and inscrutable. Both interrupt the flow of words, causing the presiding uses of language to break down. Both radiate outwards, as contagious energies that forge communal bonds, and bring about unreasonably collective modes of embodiment.

This essay was published by the feminist film journal Another Gaze, to accompany an online screening of ‘A Question of Silence’ at Another Screen. An earlier version of the text was presented at the SOUND :: GENDER :: FEMINISM :: ACTIVISM conference organised by the Graduate School of Global Arts (Tokyo University of the Arts) and Creative Research into Sound Arts Practice (University of the Arts London), at Chinretsukan Gallery, Tokyo, in 2019. A version was also presented as part of the public lecture program for Elena Vogman’s theory seminar at the Weissensee School of Art, Berlin, in 2020.

[1] Gorris had initially approached director Chantal Akerman with the screenplay, but since Ackerman was overcommitted with her own projects she apparently suggested that Gorris do it herself, assuring her that “directing isn’t all that difficult.” Later, Gorris’s 1995 film Antonia’s Line would become the first female-directed feature to win an Academy Award (in the category then still known as Best Foreign Language Film).

[2] “Hepeating” is a word that gained some traction in recent years on social media, to name this still all-to-familiar scenario, which was also parodied in a Punch cartoon where one woman sits in a boardroom meeting with five men, and the caption reads, “That’s an excellent suggestion, Miss Triggs. Perhaps one of the men here would like to make it.” See also: “whitepeating”, when white people take credit for what people of colour said first, or when the words are only heard when repeated by white people.

[3] Jane Root, “Distributing ‘A Question of Silence’: A Cautionary Tale” in Screen (Volume 26, Issue 6, November-December 1985) pp 58–64. The UK distributor Cinema of Women (COW) ran as a feminist collective from 1979 until 1991, releasing a number of feature films and documentaries by filmmakers including Pat Murphy, Heiny Srour, Lizzie Borden, Lynne Tillman and Sheila McLaughlin, Margarethe von Trotta, Leontine Sagan, Audrey Droisen, and Michelle Citron. See Julia Knight, “Cinema of Women: The Work of a Feminist Distributor” in Doing Women’s Film History: Reframing Cinema Past and Future ed. Christine Gledhill and Julia Knight (University of Illinois Press: Urbana, Chicago and Springfield. 2015). Much of COW’s archives, including their files on Gorris’s A Question of Silence, are available via the Film and Video Distribution Database (FVDD) at http://fv-distribution-database.ac.uk.

[4] All quotes taken from Jane Root, “Distributing ‘A Question of Silence’” Op Cit. except for Stanley Kaufman, “Jaundice Posing as Justice” in The New Republic, September 3 1984, pp 24-25.

[5] Conversation with the author, 20 September 2019.

[6] Carson, Anne, “The Gender of Sound” in Glass, Irony, and God (New Directions Publishing, 1995), pp 119-142.

[7] Carson, Anne, “Variations on the Right to Remain Silent” in Float (Jonathan Cape, London, 2016) not paginated.

[8] Kafka, Franz, “Letter From January 8 to 9, 1912 [1913]” in Letters to Felice, eds. Erich Heller and Jürgen Born, trans. James Stern and Elisabeth Duckworth (Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2013) pp.145-148.

[9] Mavili Collective was formed in 2010 with a stated commitment to “produce nomadic, autonomous collective cultural zones that appear and disappear beyond the logics of the market”. See https://mavilicollective.wordpress.com/ (last accessed 1 September 2019).

[10] Accessed https://youtu.be/TYva1Q-u4bk 1 September 2019.

[11] Accessed https://vimeo.com/352083590 10 January 2020.

[12] Kruger, Barbara, “A Question of Silence” in Artforum (Summer 1983, Vol. 21, No. 10).

[13] Woolf, Virginia, “The Value of Laughter” (1905) in The Essays of Virginia Woolf : vol. 1: 1904–1912, McNeillie, Andrew (ed.) pp.58-60.

[14] Cixous, Hélène, “The Laugh of the Medusa” (trans. Keith Cohen and Paula Cohen) in Signs, Vol. 1, No. 4 (Summer, 1976), pp. 875-893.