Film still: Pauline Boudry / Renate Lorenz, Silent, 2016, video, 7 min. Performance: Aérea Negrot. Courtesy of the artists and Marcelle Alix, Paris / Ellen de Bruijne Projects, Amsterdam.

Film still: Pauline Boudry / Renate Lorenz, Silent, 2016, video, 7 min. Performance: Aérea Negrot. Courtesy of the artists and Marcelle Alix, Paris / Ellen de Bruijne Projects, Amsterdam.

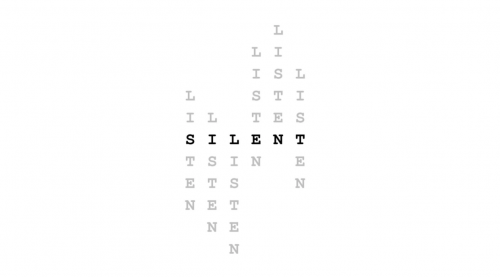

I’ve written several things around silence over the last year (including texts on Terre Thaemlitz, Ultra-red, and A Question of Silence by Marleen Gorris). This was a talk I gave following a screening of Pauline Boudry & Renate Lorenz’s 2016 video Silent (for clip club at District Berlin), in which the brilliant Aérea Negrot appears surrounded by microphones on a rotating stage at Oranienplatz in Berlin’s Kreuzberg, and remains silent for around four minutes and thirty three seconds …

The silence that Aérea Negrot performs in Pauline Boudry & Renate Lorenz’s video Silent (2016) demands that we see it as more than a homogeneous absence. In a single shot, we watch the vocalist move through a richly textured procession of silences–some of them private and inscrutable; others lush and expressive. We see agency, strength and pleasure, as well as traces of vulnerability and pain. There’s hesitation, preparation, flirtation, awkwardness, and amusement. There’s contemplation, there’s distraction, and there’s disinterest.

At one point, Negrot smokes a cigarette with a sort of cinematically coquettish contempt, blowing smoke into one of the microphones in front of her, instead of giving her voice to it. Later there’s a moment of extreme pathos, as the silent singer wipes tears away from her eyes. What registers at first as something like stage fright, then starts to appear more like an active strategy, with silence emerging as a conscious technique of delay and refusal. Throughout, there’s a fluidity across and between not being able to say, not being ready to say, not being permitted to say, not knowing what to say, not wanting to say, wanting not to say, and wanting to be attuned to the unsayable.

Silence isn’t simply a problem to be overcome – it’s also a solution to the problem that is presented by the array of microphones pointing in the performer’s face. There are no less than ten mics following her on the rotating state, all varied models, presenting a spectrum of technologies, as if to ensure total capture of her voice. There is of course violence in having one’s voice silenced, but there can also be another sort of violence in being forced to speak, and one way to respond to the burden of enforced speech is to hold on to one’s silence, to try to find what the poet M. NourbeSe Philip has called “a silence other than the one that is imposed.”[1]

Negrot interacts with the demanding mics in front of her several times throughout her performance of silence. She taps one of them for a mic test, as if she’s about to begin, but then she decides against it. She grabs a few mic stands, half-heartedly tries to adjust them, but then changes her mind. She leans into one of the mics, poised to speak, but then she moves over to lean into a different one, and then a different one, and then she gives up – there’s too much choice, too many microphones, too much expectation.

After about 4 minutes and 33 seconds of Negrot’s silence, a song starts. At first it’s acousmatic and disembodied, but then we cut to the performer sitting on a bench, in the same public square, now off-stage, away from the microphones, with her private headphones in her ears, singing a song that she composed specifically for this work by Boudry & Lorenz. “Dear president,” she sings “You have no arms no head no legs and no sense” “your enemy is your lover, I need make-up, underwear, and hormones”, “dear visitor, are you optimistic, when our country is at war?” “what is the difference between museum, artwork, and enemy? it sounds all the same to me”.

Silence and sound are not mutually exclusive here, they exist in and through each other. The silence can be full of expression, while the words can carry layers of opacity. One can withheld speech in front of the microphones, but then break into song offstage, with lyrics that include demands for trans rights, and hints at some kind of art institutional critique where museum, artwork and enemy are blurred into each other (keeping in mind that this work is most often seen as part of a video installation in museums and galleries) …

I just mentioned that the duration of the silence before the song starts is around 4 minutes and 33 seconds, and if you do see this work installed in an art institution, when you read the wall text you find an explicit reference to John Cage’s iconic ‘silent piece’ 4’33” (1952). Cage’s composition was originally inspired by his friend Robert Rauschenberg’s White Paintings (1951). Cage saw these blank white canvases as “landing strips” for shadows and dust, whereby the absence of the picture created a situation in which the painting’s unauthored and always-shifting environmental conditions could be perceived in new ways. In a similar spirit, 4’33” was supposed offer an emptied-out sonic field, through which audiences would attune themselves to the incidental sounds of the surrounding environment.

Cage originally conceived the score for classical concert halls, which are spaces where a particular sort of silence is predetermined by the etiquette that requires audiences sit quietly and attentively for the duration of a performance, until it’s time for them to applaud. In contrast, Boudry & Lorenz’s Silent was recorded outside, in public space, where the silence is much less loud, because it’s in the midst of passers-by who may or may not even notice that a performance is happening.

The film was shot at Oranienplatz, the public square in Kreuzberg that has been a crucial gathering point and symbolic centre of the OPlatz refugee protest movement. The movement dates back to 2012, when precarious and undocumented migrants and asylum seekers around Germany travelled to the capital, in defiance of the residence obligation that prohibited those seeking asylum from leaving the districts assigned to them. From 2012 until 2014, thousands of activists and supporters were part of a protest encampment occupying the square.

Tribute to Napuli Langa at Oranienplatz, Berlin, September 2021. Photo: A. Groom.

Tribute to Napuli Langa at Oranienplatz, Berlin, September 2021. Photo: A. Groom.

The tents were forcibly cleared in 2014 – two years before Lorenz & Boudry filmed Silent – but over the years the square has been intermittently reactivated as a refugee rights information point and centre for community gathering and public actions. Just last month, the activist Napuli Langa climbed one of the large sycamore trees in the square and she sat in its branches, in the rain, for six days, until the Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg district was forced to grant refugees the permanent right to protest at the square. This was a re-enactment of a five-day protest she had done back in 2014, during the evacuation of the camp, when she climbed the same tree and stayed there until the district granted open-ended approval of the right to continue protesting at the site.[2] Seven years later, when they tried to rescind this decision over a bureaucratic formality, Langa went back up into the branches and refused to come down until the district reinstated a legally binding approval of the right to protest at Oranienplatz.

So this is a highly contested public site, far removed from the decontextualized concert hall for Cage’s original 4’33”, a hushed and closed-off space that could be anywhere. Cage had also been interested in taking 4’33” out of its initial context in the concert hall. There are recordings of the empty composition which he made in his Sixth Avenue apartment, with the ambient sound of the city playing out as background turned into foreground. But Cage’s project always tended toward the transcendental.[3] According to the composer, what he liked about listening to the traffic outside was that he could experience it as pure noise, without any contamination from narrative, style, or technique – without, in his words, “the feeling that someone is talking”[4] …

But of course someone is talking! The sound of the city is the sound of an amalgamation of subjects, messages, talents, intentions, feelings and techniques. What a feat it was for him to drain all this out! A feat that depended on an active denial of complexity, and a particular sort of subject position – one that was able to experience the soundscape of Manhattan as completely depersonalised and frictionless, to hear the alarms and sirens as neutral and devoid of narrative, and to imagine that emptiness could be smooth, universal, and uncluttered by specificity.

Charlotte Moorman’s setup for John Cage’s 26′ 1.1499″ for a String Player at WNET studios, 1974. Courtesy of Charlotte Moorman Archive, Northwestern University Library.

Charlotte Moorman’s setup for John Cage’s 26′ 1.1499″ for a String Player at WNET studios, 1974. Courtesy of Charlotte Moorman Archive, Northwestern University Library.

Speaking of cluttering, I’m going to turn to this image showing the cellist and performance artist Charlotte Moorman’s set up for a performance of Cage’s composition 26’1.1499”, on public television in 1974. 26’1.1499” was a composition for a solo string player, from 1953. Like 4’33” from the previous year, this piece was named after its intended duration, twenty-six minutes and 1.1499 seconds. It was not an empty composition, like 4’33”, but in both pieces the self-referential, numerical title was meant to keep external meaning and narrativization at bay. Also in keeping with the ethos of 4’33”, there were parts of this score which required interpretative collaboration from the performer, who was explicitly called upon to bring extra-instrumental and non-musical noises into the performance.

As she worked on 26’1.1499” throughout the 1960s and 70s, Moorman gradually contaminated its contents with spoken word interventions, where she would recite fragments of text that she collected over the years. As music historian Benjamin Piekut has chronicled, various clippings from newspapers reports, advertisements and other ephemera were stuck into the pages of Moorman’s score––including instructions for how to insert tampons; an advertisement for comfortable women’s underpants; a classified birth control announcement from Planned Parenthood; the title of the 1965 film How to Murder your Wife; as well as newspaper articles about Watergate; cuts to Medicare benefits for the elderly; and an attempted rape on a university campus. There’s also a page in Moorman’s version of the score where she lists ideas for “other sounds”, with a sub-entry on “people sounds” which includes: orgasms, laughs, newborn baby cries, hiccups, and “flatulent lady.”[5]

The photograph of Moorman’s set-up for a performance of the piece on public TV (above) shows colourful trinkets, toy missiles, balloons waiting to be popped, and, at the front of the stage, a carton of eggs which would be fried during the performance–all indicating a scene of exuberant cacophony that would be entirely at odds with Cage’s serene abstractions. And indeed, Moorman’s work was met with strong disapproval from Cage and his inner circle. In 1964 the composer’s friend Jasper Johns wrote to him in a letter that “C. Moorman should be kept off the stage.” In 1967 Cage commented that he thought she was “murdering” his piece, and in an interview in 1991 he recalled “I didn’t like it at all. And my publisher said, the best thing that could happen for you, would be that Charlotte Moorman would die.”[6]

They despised what she was doing, but from her perspective she was being wholly faithful to the composer’s principals. Her copy of the 26’1.1499” score includes a handwritten note reminding her of the Cagean principle, “There is no such thing as silence. Something is always happening that makes a sound.” And this 1974 photograph of her performance set-up shows a prominent framed portrait of the composer, smiling back at the TV audience. Perhaps at this point her relationship with the figure of John Cage had gone beyond earnest tribute and into something more like conscious trolling, but the fact is that her development of the 26’1.1499” piece did not transgress its instructions. The score explicitly calls for sounds other than those produced on the strings of the instrument, and this prompt is explicitly left open to interpretation by the performer.

It’s really Cage who transgresses his own stated principals when he dictates what should or shouldn’t be included in performances of his work. He was interested in chance and open-endedness, but then he was weirdly prescriptive about what that could mean. He was unconventionally generous in the amount of interpretive freedom that he granted to performers of his work, but then, as he once qualified, he also felt that “When this freedom is given to people who … remain people with particular likes and dislikes, then, of course, the giving of freedom is of no interest whatsoever.”[7]

He wanted to open the work up, to break down the boundaries between the art and the life surrounding it, between what counts as music and what doesn’t, between the artist’s intentions and the incidental sounds of the world. But then he insisted that the world which penetrated the frame remained uncluttered, so that when a woman brought in content relating to menstruation, contraception, abortion, rape and femicide, she was “murdering” the work, and the best thing that could happen for the work at that point would be “for her to die”. The work should be open to the world, says Cage, but open only in a specific sort of way––and only to a specific sort of world. Basically: anything can be music and anyone can make music, but please no flatulent ladies!

*

In a 1977 essay for Artforum, the feminist art historian Moira Roth identified Cage and a selection of other influential downtown New York white male artists from the 1950s and ‘60s as proponents of what she termed the “aesthetic of indifference.”[8] Trying to come to grips with their valorisation of negation and passivity during the McCarthy period, she emphasised the pervasive sense of political paralysis that many Americans felt during this era of hysterical patriotism and persecutory right-wing fervour.

Later, in the 1990s, after Cage had died, the queer theorist Jonathan D. Katz drew out Roth’s analysis while considering the sexual politics of Cagean silence.[9] Katz reminds us that the McCarthy era was characterised not only by anti-communism but also by rampant homophobia. The Red Scare overlapped with a Lavender Scare in hateful cultural anxiety about America’s dangerously invisible enemies who could operate in society’s midst. According to this paranoic current, the queers and the commies were enemies who could hide in plain sight, recruiting new members and corrupting family values from within—so fighting their existence meant first detecting and exposing them.[10]

Silence, in this context, was obviously highly complicated. It was a protective shield, but it could also energise the homophobic hatred, because the same silence that was imposed was also perceived as a power and a threat. For Katz, we should understand Cage as part of a pre-Stonewall generation of gay man in America, for whom silence was a strategy of subsistence, a symptom of oppression, and also potentially a space of oppositional existence.

Towards the end of Cage’s life, silence would become amplified as a queer political issue during the AIDS crisis. A brutal unspeakability had long been enforced around “the love that dare not speak its name” —instilling shame and confusion, feeding into fear and censorship, leaving abusers unaccountable, depriving queers of their history. With AIDS the silence became literally lethal, and the rallying call Silence=Death would become synonymous with the AIDS activism movement. Cage, evidently unwavering in his commitment to the “aesthetic of indifference”, wanted nothing to do with this explicit politicization of silence. When he was confronted by a protestor chanting “silence equals death” during a public symposium on his work, not long before he died in 1992, his response was to say, airily, “in Zen, life equals death.”[11]

SILENT|LISTEN graphic courtesy of Ultra-red.

SILENT|LISTEN graphic courtesy of Ultra-red.

I have written elsewhere about this graphic by the sound artists and political organisers Ultra-red, which shows us that the word silent and the word listen are made up of the same letters. SILENT|LISTEN was one in a series of works where Ultra-red re-purposed the durational frame of Cage’s 4’33”, taking it up as a critical tool for recording and processing the history and ongoing ramifications of AIDS – performing the composer’s ‘silent piece’ with a mic in hand at various sites of queer resistance and protest in Los Angeles, and building what they called an ‘Archive of Silence’ from a series of public meetings where survivors would gather and listen together to the framed silence of 4’33” before discussing the AIDS crisis, “where it has been, where it is now, and where it is going”.[12]

As with Ultra-red’s use of 4’33”, Boudry & Lorenz’s Silent makes for a drastic departure from Cage’s high modernist end-game gesture. While Cage promoted an aesthetic of transcendent anti-expressionism, Negrot’s performance of silence is unapologetically expressive, and clearly situated in a particular body at a particular site with its particular inscriptions and particular erasures of ongoing political struggles. But neither Ultra-red nor Boudry / Lorenz / Negrot had to subvert the basic proposition of 4’33”; while honouring the principle that silence is a precondition for listening, their works expand the application of the durational frame, to affirm that practices of listening to what is not there – or not meant to be there – can allow for things to be heard in new ways.

Film still: Pauline Boudry / Renate Lorenz, Silent, 2016, video, 7 min. Performance: Aérea Negrot. Courtesy of the artists and Marcelle Alix, Paris / Ellen de Bruijne Projects, Amsterdam.

Film still: Pauline Boudry / Renate Lorenz, Silent, 2016, video, 7 min. Performance: Aérea Negrot. Courtesy of the artists and Marcelle Alix, Paris / Ellen de Bruijne Projects, Amsterdam.

An earlier version of this text was published as a chapter titled “Organise the Silence” in the book Master of Voice, edited by Lisette Smits and published by Sternberg Press in 2020. The book came out of the Master of Voice MFA program at the Sandberg Institute in Amsterdam (2016-2018), where I worked as Theory Tutor. I also presented a version of the text as a lecture for the program Unseen and Unheard, presented by Cashmere Radio as part of Howling Wolf Festival in Berlin in 2019.

[1] M. NourbeSe Philip, “Dis Place – The Space Between in A Genealogy of Resistance and Other Essays” (1997), republished in Bla_K: Essays & Interviews (Book Thug, Toronto, 2017), 275.

[2] An account by Napuli Langa on the Oranianplatz protests and the 2014 tree occupation can be found here https://movements-journal.org/issues/02.kaempfe/08.langa–refugee-movement-kreuzberg-berlin.html See also “Contested Spaces The Oranianplatz Protests, Berlin, 2012-2014” in Steinhilper, E., Migrant Protest: Interactive Dynamics in Precarious Mobilizations. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2021.

[3] A text he wrote for an exhibition of Rauschenberg’s White Paintings reads, “To Whom / No subject / No image / No taste / No object / No beauty / No message / No talent / No technique (no why) / No idea / No intention / No art / No object / No feeling / No black / No white (no and).”

[4] See “John Cage – About Silence and Traffic” accessed www.youtube.com/watch?v=H-Xy-gAaOzw February 2019.

[5] Piekut, Benjamin, Experimentalism Otherwise: The New York Avant-Garde and Its Limits (Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press) pp 154-155.

[6] ibid, pp 149-150.

[7] Cited in Kostelanetz,Richard, Conversing with Cage, New York: Limelight Editions, 1988, p. 67.

[8] Roth, Moira, “The Aesthetic of Indifference” in Artforum, November 1977, 46-53

[9] Katz, Jonathan D. “John Cage’s Queer Silence; or, How to Avoid Making Matters Worse” in GLQ 5:2 (1999) pp 231-252.

[10] See Johnson, David K., The Lavender Scare: The Cold War Persecution of Gays and Lesbians in the Federal Government, Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2004.

[11] Jones,Caroline A.,“Finishing School: John Cage and the Abstract Expressionist Ego” in Critical Inquiry, Vol. 19, No. 4 (Summer, 1993), pp. 628-665; 665.

[12] Ultra-red, SILENT|LISTEN (The Record) (2006). I wrote about Ultra-red’s uses of silence and 4’33” here.