When the Mona Lisa went to Washington, DC in 1963, it was the first time The Louvre had ever allowed her to travel abroad. The circumstances were exceptional: basically, André Malraux was smitten with Jacqueline Kennedy. She, America’s then-First Lady, and he, France’s then-Minister of Cultural Affairs, had first met in Paris in the spring of 1961. They spent a day together, visiting museums and speaking in French about art. Dazzled and eager to please, Malraux somehow made a spur-of-the-moment promise that da Vinci’s flimsy little picture would visit the US capital, IRL.

Surrounded by draped red velvet and guarded around the clock by US Marines, the Mona Lisa attracted ten thousand visitors to the National Gallery of Art on her first day there—and in the weeks that followed, and the museum had to extend their opening times to try to accommodate the crowds. In the midst of the media frenzy surrounding the event, Andy Warhol wondered why the French hadn’t just sent a copy. “No one would know the difference,” he remarked. And if no one knew the difference, what would the difference be? By sending a copy instead, The Louvre could allow everyone to experience a direct physical encounter with something that looked the same, while also keeping the original safely tucked away, preserved for posterity.

This was in fact the exact thinking that led to the closure of the Lascaux caves in the south of France, and the production of a facsimile nearby. Malraux took the Mona Lisa to Washington in January of 1963, and three months later his ministry was closing the Lascaux caves off from the public, in the name of preservation.

The paintings at Lascaux had survived for more than seventeen thousand years, but they threatened to disappear forever as soon as we got too close. As early as 1955, less than a decade after the site was opened to the public, contamination caused by the near-constant swarms of breathing humans was starting to show. The thought of accidently losing the pictures was evidently too much for us to bear—we had to lose them on purpose, by resealing the caves and replacing them with a likeness of our own making.

Plans for Lascaux II were drawn up, and a team of painters and sculptors began work on reproductions of several sections of the caves, with every contour and every mark replicated to the millimeter. The copy finally opened to the public in 1983, two hundred meters from the original site. Now nobody sees Lascaux I, but hundreds pass through the underground simulacra-sequel every day.

I’m deep underground, inside the Ōtsuka Museum of Art. Built into a hillside at Naruto, a small coastal town in southeast Japan, the museum has more than a thousand iconic works on permanent display. There’s da Vinci, Bosch, Dürer, Velázquez, Caravaggio, Delacroix, Turner, Renoir, Cézanne, van Gogh, Picasso, Dalí, Rothko—all the Western canon’s greatest hits. Even Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel frescos are here, lining the walls of a custom-built hall.

To “acquire” the works in this collection, a technical team prints photographs of them, in full scale, onto ceramic plates. They then fire the plates at 1,300 degrees centigrade and follow with some hand-painted touch-ups. According to the museum’s marketing material, these painted-photographed-printed-baked-painted pictures will then survive for several millennia. “While the original masterpieces cannot escape the damaging effects of today’s pollution, earthquakes and fire,” reads a statement from the museum director Ichiro Ōtsuka, “the ceramic reproductions can maintain their color and shape for over two thousand years.”1

The hundreds of millions of dollars that have gone into this enterprise came from the pharmaceutical company Ōtsuka Holdings—which is also behind the popular antipsychotic drug Aripiprazole, and the popular Japanese beverage Pocari Sweat. The museum’s full-time guide is a friendly faceless blue robot named artu-kun—“Mr. Art”—whose belly is branded with the Pocari Sweat logo. Part of his job is to remind visitors that it’s okay to touch the artworks here, since they’re indestructible objects.

Everything in this enormous underground museum is simultaneously anticipating and defying destruction. Has the apocalypse already happened, or are we still preparing for it? From inside the bunker, it’s impossible to tell. Looking at the ceramic reproductions today, I am looking at them in two thousand years—there’s no difference between now and then, because history is at a standstill.

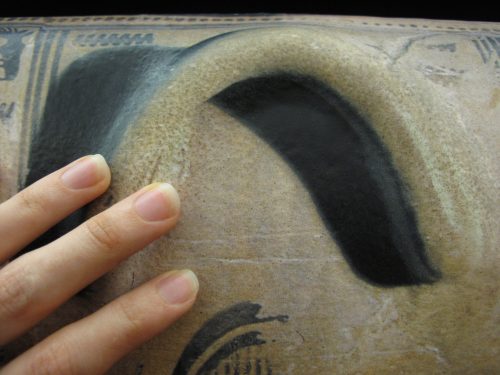

I walk around the museum, photographing and touching the artworks. I stroke the cheeks of Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring, and I press my face against Klimt’s Kiss. But the closer I get, the further away they seem. Does it still count as touching if my touch is guaranteed to have no effect?

The novelty of touching the art soon wears away, because every surface is so neutralized. The artworks start to feel like one big piece of worn-out sandpaper—and the surface of time itself is flattened into a mythic, homogeneous continuity. This is what art worthy of preservation looked like to the Ōtsuka team at the end of the twentieth century, and—if everything goes according to plan—nothing is ever going to change.

In the 1990s, while the Ōtsuka Museum was amassing its collection of everlasting copies, Jean Baudrillard was decrying what he called “the Xerox degree of culture,” where “Nothing disappears, nothing must disappear.”2 With the Lascaux caves as his recurring example, Baudrillard questioned our increasing proclivity for preservation-by-substitution, where things that would otherwise be allowed to pass are forced into artificial longevity, via their simulacra.

Evoking current debates in France about doctors artificially keeping patients alive, even when ultimate life expectancy is unavoidably short, Baudrillard used the term acharnement thérapeutique or “therapeutic relentlessness.”3 This is an apt analogy for what happens at the Ōtsuka Museum of Art: a superimposition of relentless, compulsory vitality onto artworks and europhilic art historical narratives that might otherwise have very little life left in them.

Ōtsuka has even started to take this therapeutic relentlessness a step further, by embarking on forcible revivals of the already dead. The latest acquisition for the permanent collection is their first copy of a work of art that does not exist: a painting of sunflowers in a vase, by Vincent van Gogh, which was destroyed in Japan in 1945. Along with everything around it, the painting was turned to smoke and ash during a US air raid over Ashiya on August 5–6—around the same time as the first atomic bomb exploded over Hiroshima.

But according to the brightly colored ceramic plate now on show at Naruto—which was rendered from photographs that predate the picture’s incineration—World War II never happened. In fact, according to the art history that Ōtsuka is locking into place for the next two millennia, nothing will ever happen. This is a revised and idealized version of history, with all the ruptures covered up, and all of time’s contingencies tidily sealed off. In other words, it is a version of history without a real temporality.

Let’s imagine that these ceramic boards really do survive untarnished for the next two thousand years. What would a future alien visitor then find here, amongst the ruins? It’s a history of Western art, beginning with Ancient Greece and progressing in a dead-straight line through the centuries, before finally landing at Abstract Expressionism and American Pop Art: the grand apotheosis of a three-thousand-year-long narrative. Nothing after 1970 has yet received the Ōtsuka treatment.

Of course, the more expansive any attempt at a total comprehensive overview is, the more its inherent incompleteness will show through. At Ōtsuka the feeling is one of overwhelming excess—it’s the largest museum in Japan and seeing everything means walking for almost four kilometers—as well as alarming omission. For instance, there are hundreds and hundreds of works, but the female artists who have been invited into this grand narrative can be counted on one hand. Initially I thought this would begin to improve, at least a little, as I moved along Ōtsuka’s chronological progression of art from antiquity up to the 1960s—but I found that the only non-male artist who appears in the postwar era is Bridget Riley.

This is a version of art history with no sculpture, no video art, no performance or installation art, no ready-mades—only flat photographically reproduced paintings and some other things that are made to look like flat photographically reproduced paintings. A selection of medieval tapestries and Byzantine mosaics are included, as photographs fired onto ceramic boards—their textures completely flattened out. Stranger still are some Ancient Greek vases which have been photographed from all sides and printed as two-dimensional rectilinear planes, with shadows from the handles included as part of the image surface, indicating their former three-dimensionality. But although everything here depends on photographic technology, this is a history of art in which photographs have never featured as artworks in themselves. The camera is simply a vehicle that transfers images from surface to surface; it does not make its own images.

In Mr. Ōtsuka’s statement about the museum, he proudly announces that visitors can now finally “experience art museums of the world while being in Japan.” But if this is really about increased accessibility, we might wonder why the artworks that are selected for reproduction are already some of the most widely reproduced and accessible images of all time. The museum opened at the turn of the twenty-first century, by which point anybody with an internet connection anywhere in the world would be able to access any of these iconic images, sometimes with resolutions that reveal more detail than our naked eyes could ever see.

As a mode of reproduction, photography invites multiplicity, fragmentation, and circulation. Writing in the 1940s, Malraux observed that the photographic document can liberate the object from its context and hierarchical positioning, as well as from its physical volume and prescribed dimensions.4 But unlike Malraux’s “museum without walls”—and unlike Taschen books or Google Art Project—the Ōtsuka team returns volume, weight, and location-specificity to the mechanically reproduced work of art. They turn dematerialized images back into singular, heavy objects with fixed dimensions and spatial positions, so the images don’t travel to us—we have to travel to them.

If Ōtsuka’s ceramic board copies actually fulfill the promise of surviving untarnished until the year 4016, they will almost certainly outlive the originals they refer to. More than duplicates, they’re replacements. Their aim is to permanentize pictures and histories that are relatively fragile and transient.

When the Umbria and Marche earthquake struck central Italy in 1997, destroying much of the thirteenth-century frescoes in the Basilica of St. Francis in Assisi, the Ōtsuka team offered to lend their newly acquired photographic versions of the frescos to the Italians, for consultation during the restoration process. The original could then be rendered as a copy of its own copy—and every time its material veers away from what it was, consultation with the allegedly indestructible simulacra can bring it back into line.

There is a broader issue here, which is about finding ways to look at artworks without taming their dynamic and durational capacities. When art historians seek to pin down works of art to a single date of authorial inception, the temporal multiplicity of the work is denied. Likewise, when conservators imagine returning a work to the condition of the “artist’s original intentions,” they fight against the ongoing durations of art objects—objects which always accumulate marks of their historical and material realities.

The Tate Modern’s 2013 retrospective for Saloua Raouda Choucair included an abstract painting that was riddled with holes and had shards of glass sticking out of it, as a result of a bomb going off near the artist’s home during the Lebanese civil wars. She had decided to leave the canvas unrepaired, so it could continue to bear witness to the violence that it had endured. The ruptured abstract composition thus took on a direct indexical relation with the external world. The picture pointed not just to a moment of artistic creation in the past, but also to what it had been through since then—so its temporality extended beyond the initial instance of creative authorship.

But the Ōtsuka Museum of Art is founded on an attempt to deny the passage of time. There is no past here, since nothing passes away and all the scars of history can be covered up, and there is no futurity, since there is no space for contingency or chance. In this archive there is only the relentless, permanentized present, preempting any alternate future, replacing everything else with itself, enforcing more of the same forever.

Adorno observed that the words “museum” and “mausoleum” are “connected by more than phonetic association.” The German word “museal” (museum-like), he wrote, “describes objects to which the observer no longer has a vital relationship and which are in the process of dying.” Such objects go to the museum when they are ready to withdraw from life. In Adorno’s words, “They owe their preservation more to historical respect than to the needs of the present.”5 But is there not also potential for strategies of reactivation within the museum-mausoleum? Can’t we try to think about ways of setting its contents in motion, in accordance with the needs of the present?

As I was struggling to find my way out of the Ōtsuka Museum of Art, I started to become more aware of the seams that run through its pictures. Because the fired ceramic boards can only be produced up to a certain size, any larger surfaces have to be pieced together from separate plates. As a result, many of the pictures feature strange disjunctive grooves, which remind us of their base materiality.

The more I focus on these caesurae, the more the museum’s myth of solidity and clean continuity is disturbed. The hyper-durability of the baked ceramic plates comes with a compromise of surface interruption, and it is in the surface interruptions that we find evidence of the gaps that run through all versions of history—even and perhaps especially those that present themselves as watertight. Looking at the spaces in between the pieces—spaces we are not supposed to look at—I wonder what potentiality lies there. What leakages might pass through these openings? And how can the visible seams be taken up as an invitation to rearrange the contents of the archive?

Certainly, the Ōtsuka Museum of Art is a corporate vanity project, which presents its reactionary version of art history as something conclusive and unchanging. It fetishizes individual (white male) genius, perpetuates simplistic progress narratives, costs too much money, takes up too much space, and fails to properly deal with the temporality of the art that it cares for. But which of our major art institutions are exempt from such criticisms? In its excessive permanence and false totality, Ōtsuka is simply reproducing the problems encountered in contemporary museological, art historical, and preservation practices more generally. In this respect, the Ōtsuka Museum could also be considered the most elaborate work of institutional critique ever attempted.

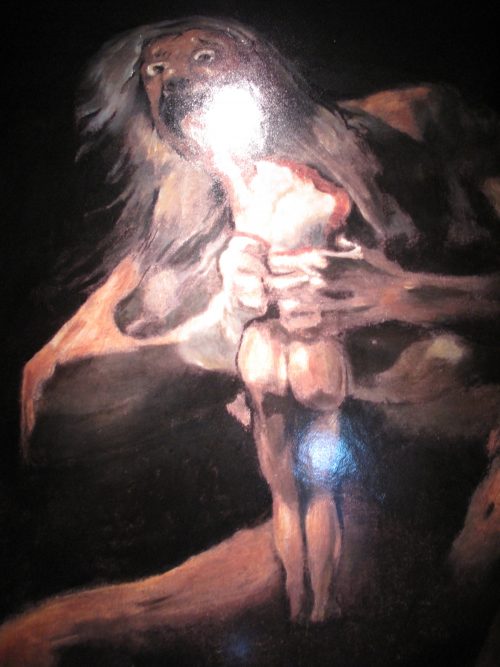

Still trying to find the exit, I stumble into a darkened room with reproductions of Goya’s Black Paintings, and I stop in front of Saturn Devouring His Son. It’s a truly appalling image: a naked, cowering old man with bulging eyes looking right back at us, and a half-eaten child clenched in his knuckly fists.

Saturn is the Romanization of Cronus, the Greek god of time whose image later morphed and amalgamated into the bearded, scythe-carrying old man known as Father Time. The myth of Cronus tells us that he had castrated and overthrown his own father, and so he was terrified that one of his children would one day do the same to him. To prevent this from happening he would consume them as soon as they left their mother’s womb.

The paranoid patriarch struggles to hold on to his position of power by desperately suppressing all futurity. He devours everything that could come after him, in a precautionary measure against the inevitability of change. This is an image of time that exists only as a perpetual, cannibalistic present, preemptively replacing any alternative with itself. There’s no real future in this version of time, since there is no indeterminacy, no contingency—only prediction and subsumption.

But Cronus’s struggle is ultimately futile—and somehow in Goya’s depiction he seems to know it. Rhea—who is Cronus’s wife, and sister—eventually makes a plan with Gaia, their mother. When Rhea gives birth to the sixth child, Zeus, the women hide the baby away—and they later force Cronus to disgorge the contents of his stomach, so that one by one the other infants are vomited back to life.

Here we are reminded that the future is not just something “in the distance” that we identify and move toward in a linear fashion; it can be unrealized potentiality that is already present, but suppressed. This futurity can be swallowed and withheld—but then it can be spewed up and redistributed. By intervening in Father Time’s system of control, it is the mothers in this myth who can restore the future’s messy indeterminacy.

An earlier version of this text is published in the book ‘La vie et la mort des œuvres d’art / The Life and Death of Works of Art’, edited by Christophe Lemaitre and published by Tombolo Presses, France, 2016 (in English with French translation).

Subsequently republished in e-flux journal #78, 2016 – see here.

Also republished, and translated into Dutch, for the book Pense-Bête, published by P/////AKT Amsterdam in April 2017 – see here.