On September 30, 1978, Tehching Hsieh vowed to seal himself off in a cage inside his downtown New York studio, for one year. “I shall NOT converse, read, write, listen to the radio or watch television,” he wrote, “until I unseal myself on September 29, 1979.” A friend came daily to deliver food and remove waste. This became the first in a series of arduous yearlong performance works carried out by the artist.

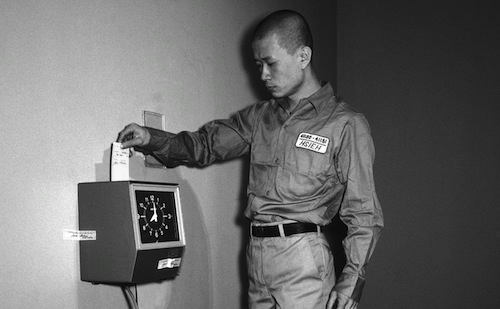

For Time Clock Piece,Hsieh punched a worker’s time clock in his studio, every hour on the hour, day and night, from April 11, 1980 to April 11, 1981. He photographed himself each time he ‘clocked in’, and the thousands of resulting images were made into a time-lapse film, condensing 365 days into six minutes. For Outdoor Piece (1981-82), he vowed “I shall stay OUTDOORS for one year, never go inside. I shall not go into a building, subway, train, car, airplane, ship, cave, tent.” Rope Piece had him tied to the performance artist Linda Montano by an eight-foot rope, from the 4th of July 1983 to the 4th of July 1984.

A few months after completing that work, Hsieh announced his No Art performance piece, for which he would not make any art or engage with anything related to art for one year. His sixth and final durational performance work was his Thirteen Year Plan (1986-1999), during which time he declared he would make art without showing it to anyone. After that, he said he would “just go on in life.” I recently emailed him with some questions.

You started out as a painter. Why did you change to live art?

There was a gradual process from painting to performance. They are my cognition of art in different times.

For your first performance piece, you jumped out of a second story window and broke both your ankles. Are you some kind of masochist?

The work is destructive, it is a gesture of saying goodbye to painting, broken ankles were out of my prediction. I have no interest in masochism.

Was physical struggle part of what you were communicating through the long duration works, or just a side effect?

The struggle is there because of the situation in life and in art, but I don’t emphasise it, my work is not autobiographical.

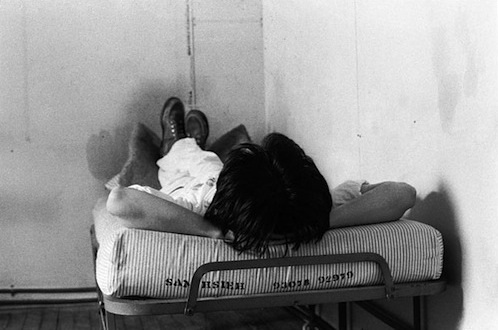

After moving from Taiwan to New York as an undocumented immigrant, your first one-year performance saw you in voluntary solitary confinement, alone in a cage without speaking, reading or writing for twelve months. Was it boring in the cage?

Staying in a cage for a few days can be boring. Staying for 365 days, it is not the same anymore and you are brought to another state of living. You need to do intense thinking to survive through the year, otherwise you could lose your mind.

Is there a particular sort of freedom to be found in self-imposed constraint?

I didn’t need to deal with trifles in daily life when staying in the cage, I had freethinking, I lived thoroughly in art time and just passed time. The freedom found in the confinement is what one could find in a difficult situation, it is a way to understand life.

Your second one-year performance Time Clock Piece is a work of monumental monotony. The thing unfolds as one big etcetera – a self-perpetuating reiteration of the same, with nothing new accomplished or accumulated. ‘Clocking in’ is the start of the worker’s day: by isolating the act and repeating it on loop, you suspended commencement and stretched it out over a whole year. Was this a conscious defiance of the notion of progress?

Punching the time clock is itself the work, I didn’t need to produce anything in the context of industrialization. The 8760 times of punching in throughout the year is repetition, but in another way, each punch in is different from any other punch in, as time passes by.

The conditions of this work meant you couldn’t ever fall asleep or leave your studio for more than an hour at once, for a whole year. It’s as if you were making literal what the anarchist George Woodcock termed ‘the tyranny of the clock’ in 1944. Were you thinking at all about the mechanised regulation of time through the worker’s body that was brought about after industrialisation?

I thought of industrialisation but that is not what I wanted to say, I’m not a political artist. Although the time clock was invented to track an employee’s working time, I used it to record the whole passing of time, 24 hours a day for the duration of one year in life, like the nonstop beat of a heart. Life time and work time are included in this one year of art time.

Unable to legally work in the US, you dressed yourself in a worker’s uniform and enacted labour without production. Can we think of this as the reductio ad absurdum of industriousness – where deadpan diligence and punctuality in the extreme amount to an elaborate emblem of inefficacy?

To me this piece approaches time from a more philosophical perspective than that of industrialisation. Instead of the 9-5 working day, the time used in this piece is the time of life. The 24-hour punch in is necessary to record the continuity of time passing. I believe Sisyphus pushes the boulder 24 hours a day, not 9–5, and he does it forever.

You have often named Sisyphus as an early influence on your practice. How did the influence manifest?

I read Albert Camus’s The Myth of Sisyphus when I was 18, and I encountered its inspiration again and again in my early age. Rebellion, betrayal, crime, punishment, suffering and freedom form a cycle in my life experience, and are transformed in art.

The other influences you have named are Dostoevsky, Kafka and Nietzsche. These are all literary figures – why did your works take the form of performance? Did you need to be outside of language?

I’m not a person using words to create, I use art, but their thoughts inspire me, and I practice in life.

What is time?

Once a child asked me, “is future yesterday?” We all ask questions about time in different ways. Time is beyond my understanding, I only experience time by doing life.

Albert Einstein: “An hour sitting with a pretty girl on a park bench passes like a minute, but a minute sitting on a hot stove seems like an hour.” Was your own perception of time altered during the one-year performance works?

My works are like a mixture of sitting on a park bench with a girl and sitting on a hot stove. This was how I felt about the passing of time.

Laurie Anderson: “This is the time. And this is the record of the time.” What’s the difference?

For me the difference is between the experience of time and the documents of time. My performances happened in real time, documents are only the record.

Very few people saw your works as they were performed; most of us will only ever have the statements and the photographic/video evidence to go by. What is the relationship between lived time and remembered time in your work? Are the documents secondary traces of the works, or an extension of them, or something else entirely?

There is invisibility in the work, even if you came to the live performances. Documents are traces of the performances. Compared with the performances themselves, the documents are the tip of the iceberg. Audiences need to use their experience and imagination to explore the iceberg under the water.

Marina Abramović has referred to you as “a master.” Her manifesto states: “an artist should not make themselves into an idol.” Have you seen her in the Givenchy fashion campaign that just came out?

I don’t really pay attention to fashion and am not sure if that means she is an idol. As a powerful artist and a beautiful person, Marina is favoured by the times. Her ambition in art is much bigger than being an idol.

Having gained a level of notoriety in the New York artworld, your fifth and final one-year performance piece was a staged negation: you stated that starting July 1st 1985 you would “not do ART, not talk ART, not see ART, not read ART, not go to an ART gallery and ART museum for one year.” Instead you would “just do life.” What is the difference between art and life?

All my works are about doing life and passing time. Doing nothing, just passing time and thinking were my mentality and I turned it into the practice of my art and life.

After this abstention from anything art-related (paradoxically carried out as art), you announced a thirteen-year plan, to commence on your 36th birthday in 1986 and continue until your 49th birthday. Your statement read “I will make ART during this time. I will not show it PUBLICALLY.” Why this resistance to being public?

After the No Art piece it seemed contradictory to go back to doing art publicly. I had to do art underground for a longer period of time, which was the last thirteen years of the millennium.

Is art without a public still art?

Art cannot exist without public, but the public could be in the future – I published the work after thirteen years.

You made such radical work, but operated so quietly. Until very recently, you were excluded from all the standard surveys of performance and body art – and then in 2009 MoMA and the Guggenheim Museum in New York both showed your work, and Adrian Heathfield’s huge monograph Out of Now was published, and there was a resurgence of interest. Why did it take so long for people to look at what you had done in the 70s and 80s?

There are reasons not in my control. My work is done in my studio or in the streets, outside the system of the art world. Most of my work was done when I was an illegal immigrant with less publicity, and the work itself is not easy to categorise. Also it is to do with my personality, but I feel comfortable with this slow and durational recognition.

You have stated that you stopped making art because you ran out of ideas. Did you say everything you wanted to say with the six completed works?

My art is not finished, I just don’t do art anymore.

Now you are “just doing life.” Will you ever make art again?

Not doing art anymore is an exit for me. Art or life, to me the quality is not much different, without the form of art, still, life is life sentence, life is passing time, life is freethinking.

This interview was published in Das Superpaper #26 March 2013